Prepared for:

Victoria Cannabis Buyers Club

826 Johnson Street

Victoria BC

Bijan Ahmadi

Academic Chair

Economics, Statistics, and UT Business, Camosun College

Stephen E. Hume

Associate Teaching Professor

Department of Economics, University of Victoria

Executive Summary:

The failure to recognize Canada’s medical cannabis dispensaries impedes access to products that represent significant savings to our health care systems. Canada’s well-established medical cannabis dispensaries serve a need in their communities, providing information and support for the marginalized and most in need. Here on Vancouver Island we have a supportive community-built supply chain that needs the opportunity to continue to expand whole-plant medicinal offerings. Until an effective operationalization of medical cannabis provision is in place, dispensaries must be provided a CDSA exemption to allow them to continue to act in the public good.

Canada is one of the few countries in the world where cannabis is treated as a legal and regulated substance; however, the Cannabis Act fails to adequately identify the different needs of the recreational and medical markets. Although the current Cannabis Regulations (SOR/2018-144) provide similar mechanisms for medical access as the now repealed ACMPR, MMPR, and MMAR, there still exists a lack of support for Canada’s well-established compassionate cannabis centres, or dispensaries. This omission is a disservice to the millions of people who use cannabis-based medicines as replacements or augmentations in their traditional treatment paths. Medical cannabis provides an inexpensive alternative to a number of pharmaceutical products that heavily tax our healthcare system through drug costs and the undesired side-effects of their use. Cannabis-based medicines have been shown to be highly effective in reducing dependence on opioids, as well as benzodiazepines, and have negligible impacts on hospital visits due to their use. Further, dispensaries provide inexpensive, safe, and informed access to cannabis-based medicine for Canadians who are being bombarded by a recreational market fueled with new technology and promise, but without the community-oriented service model that is integral to the effective distribution of cannabis as medicine. Our position paper argues that continued support is needed for dispensaries. This support will reduce pressure on the health care system and provide inexpensive access to cannabis-based products for medicine.

As the study of cannabis medicine and its economic impact is in its infancy, some research in this paper employed low sample sizes; however, the findings are significant. Powell, Pacula, and Jacobson (2017) found that “medical marijuana laws enable individuals to substitute marijuana for opiates, particularly opioid analgesics” (p. 29). Whereas Powell et al. identified significant changes in opioid use, “late adopters” of medical cannabis laws saw less impact as “these states tightly regulated dispensaries and significantly curtailed access to marijuana” (p. 33). Dispensaries that were granted more access rights contributed to “[a reduction in] opioid mortality rates by about 40%” (p. 33). If the late adopters are included, that number falls to 20%; however, both results are clearly more significant than the “relatively small” impact of having medical cannabis law in place, a reduction of approximately 5% (p. 33). Clearly, dispensaries play a significant role in access and the availability for substitution of opioids. The study by Powell et al. is important, as they clearly demonstrate “that the primary driver of the previous relationship [between medical marijuana laws and opioid deaths] was the presence of legally protected and operational dispensaries” (p. 38).

Cannabis has been shown to assist in reducing dependence on dangerous and addictive drugs like opioids and benzodiazepines. Stith, Vigil, Adams, and Reeve (2018) said that in a study of patients enrolled in MCP (medical cannabis programs) in New Mexico, 34% of patients “cease to exhibit any evidence of scheduled drug consumption” and that a further 36% “reduce[d] the number of prescriptions filled for scheduled prescription drugs” (p. 63). Although much of the research on cannabis efficacy and scheduled drug replacement focuses on opioids, which are considered “the leading cause of preventable mortality nationwide” (Stith et al., 2018, p. 63), Lucas and Walsh (2017) found that 16% of patients were substituting toward cannabis from benzodiazepines, which is significant, given that one in six Americans take this class of drugs that are “associated with an increased risk of death by suicide and accidental poisoning” (Fontanella et al., 2016, as cited in Stith, 2018, p. 63). Clearly, substituting toward cannabis not only represents a cost saving to our health care system, but reflects a decrease in preventable mortality, and a reduction in the consumption of dangerous pharmaceuticals.

Bradford and Bradford (2018) argue that access to medicinal cannabis could generate “programmatic savings . . . between $1.4 and $1.7 billion [annually]” for the United States Medicare D system (p. 461). The 24 states with medical cannabis laws had already seen an accrual of approximately $600 million in 2015 (p. 484). This represents a roughly 2% savings on total expenditures (Lew et al., 2015, p. 99). Unfortunately, the savings noted by Bradford and Bradford do not represent a “pure change in welfare” as people who choose to substitute their prescription coverage “purchase cannabis out of pocket” (p. 484).

Lucas and Walsh (2017) said that 63% of participants involved in their survey substitute cannabis for prescription medication with 32% reporting a substitution for opioids (p. 32). This is in spite of the fact that almost one third of respondents felt that obtaining authorization to use cannabis was “difficult” and costly (with 94% having to pay at least $100 for a medical recommendation) (p. 33). These findings are in line with Corroon, Mischely, and Sexton (2017) who completed a similar study in Washington state. Lucas and Walsh also identify the need to support medical access to cannabis. Only 3% of respondents were able to claim their cannabis costs to their insurance providers, although a further 3% were able to have costs covered by Veterans Affairs Canada (p. 33). This identifies the need for continued cost-effective access to medicinal cannabis products. Patients will seek out cannabis-based medicine, at whatever rate of adoption; however, Powell et al. state that “[d]ispensary allowances are associated with greater access to and use of marijuana” (p. 30), and further, that “dispensaries . . . contribute to the decline in opioid overdose death rates” (p. 33)

The substitution to cannabis would have an impact on reducing the over $300 million dollars that opioids cost the Canadian healthcare system (CCSA, 2019, p. 2). Unlike those taking potentially toxic pharmaceuticals, Gryczynski et al. (2016) determine that casual users (termed “nondiagnostic”) of cannabis represent a 16 percent lower prevalence of hospitalization than abstainers, and that even people whose cannabis use can be considered a “substance use disorder” attend hospitals at the same rate as abstainers, approximately equal to the national average (p. 15).

Support for Canadian dispensaries represents an increase in access and information to medicine that reduces costs and resource use in our medical system, improves patient well-being, and significantly reduces the impacts of harmful pharmaceuticals. Dispensaries facilitate substitution toward cannabis and are instrumental in the associated pecuniary and health benefits.

Dispensaries are not the only important part of a beneficial supply chain for medical cannabis. Aside from part 2 section 11 of the Cannabis Regulations (2018) there is little support for the protection for small scale cannabis producers, and no recognition of the symbiotic relationship between micro-cultivators and the dispensaries. This relationship is integral. Dispensaries have long-standing relationships with seasoned cultivators who have, often for years, operated outside the law to ensure continued distribution of safe and well-produced medicine for those most at need. We must not force cultivators to continue to operate in this way. Drawing from the data from years of drug policy in the Netherlands and the Czech Republic, Belackova, Maalsté, Zabransky and Grund (2015) are emphatic that “any country that is willing to implement pragmatic cannabis policies that minimize the harms to public health and safety shall keep in mind the importance of policies targeting cannabis cultivation; tolerance to small-scale cannabis cultivation has a potential to reduce the role of organized crime in the country and reduce the size of commercial market in its scope as well as size” (p. 308). This failure to effectively regulate has further

impacts. Sen (2018) argues that ineffective policy and existing illicit markets cost the Canadian Government an estimated $800 million in lost excise and sales tax revenues (p. 14), as much of the industry continues to operate outside of the legal framework. The government must recognize that small-scale cannabis cultivators are integral to the production and distribution of cannabis by dispensaries.

The benefit dispensaries offer patients has been well established in Canada. Capler et al. (2017) recommended that “future regulations should consider including dispensaries as a source of CTP [cannabis for therapeutic purposes] and address known barriers to access such as cost and health care provider support” (p. 6). Further, Capler et al. echo the findings of other researchers who show that “[n]on-profit cannabis clubs in other jurisdictions play a similar role as intermediaries between cannabis users and growers, as well as provide an alternative to markets focused on profit” (p. 6).

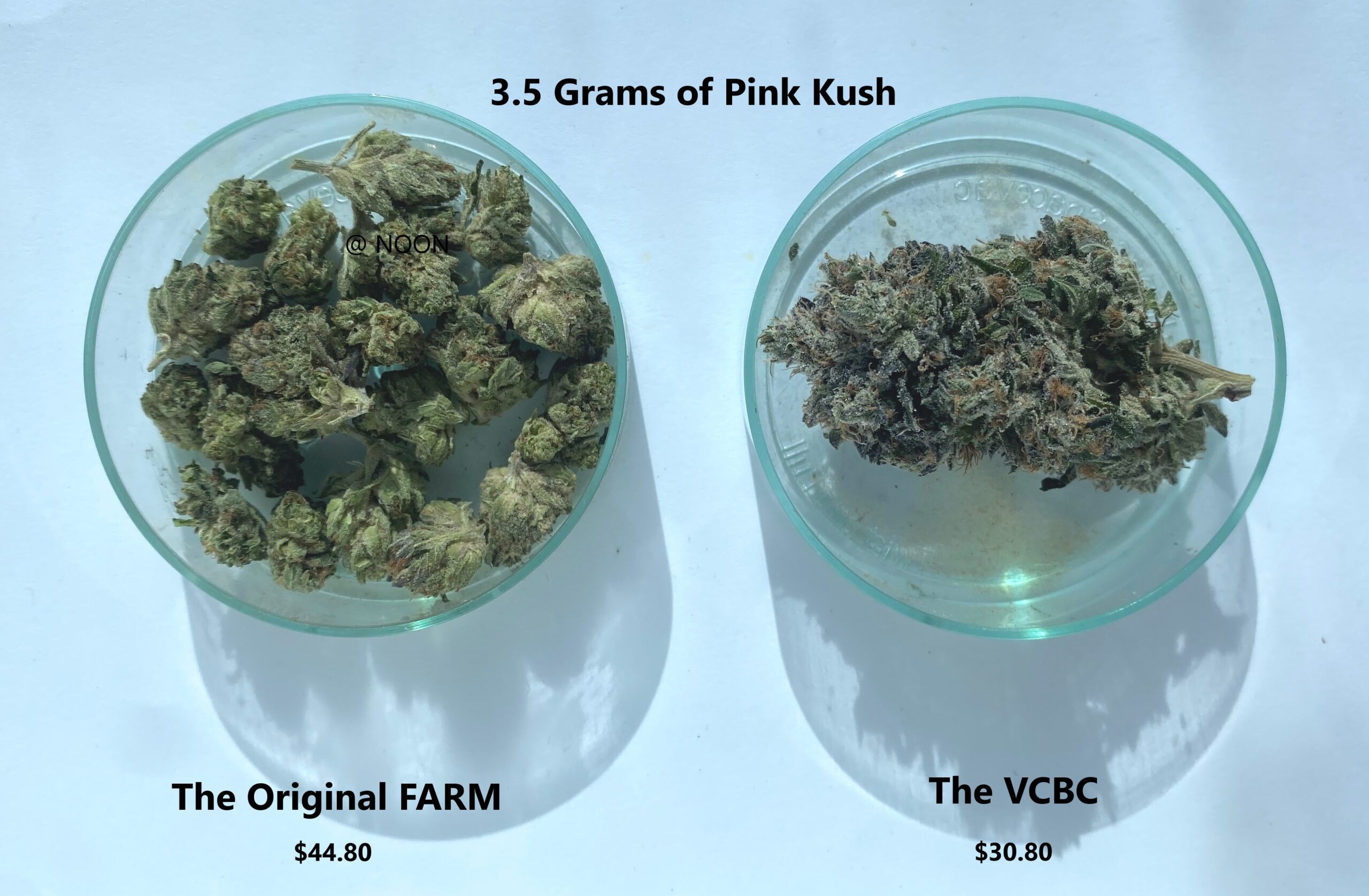

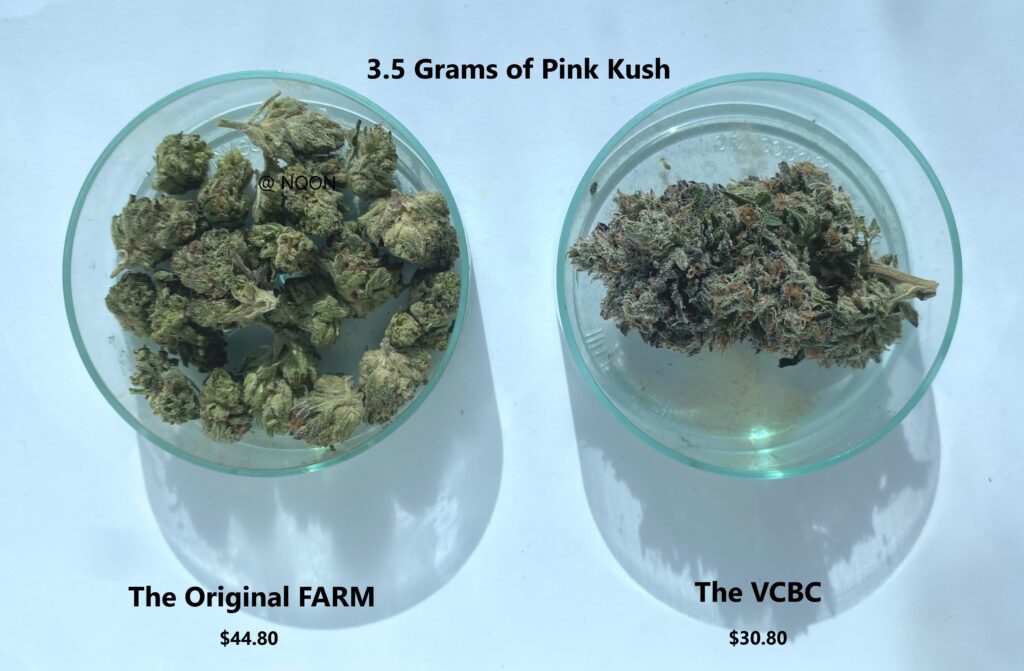

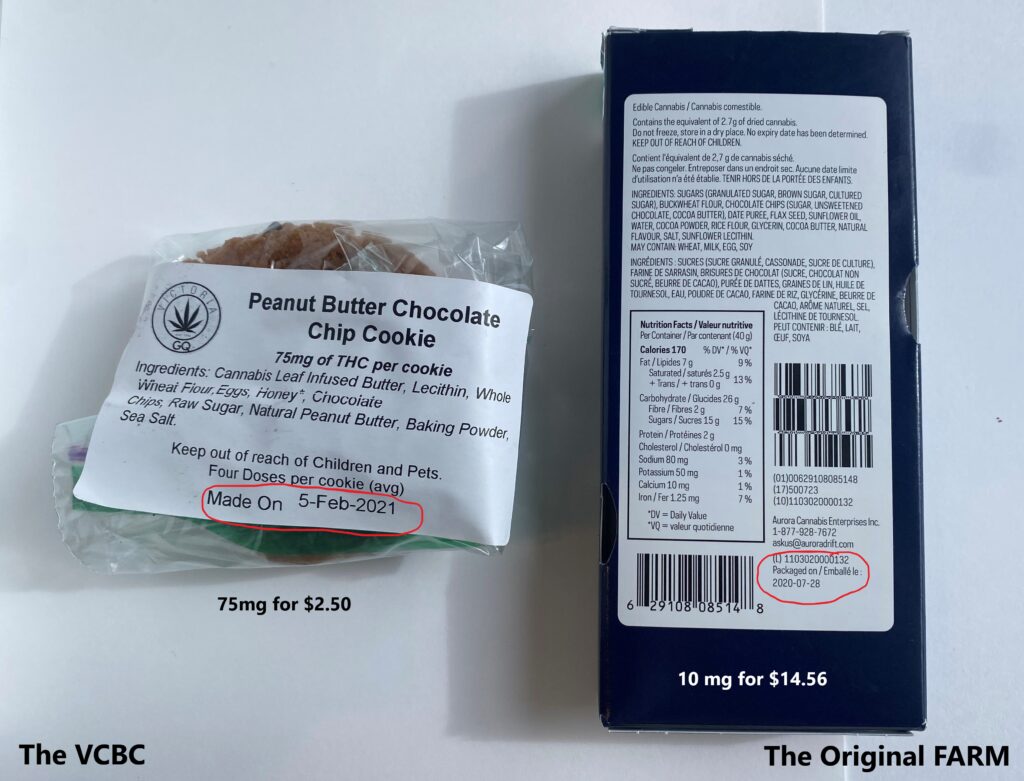

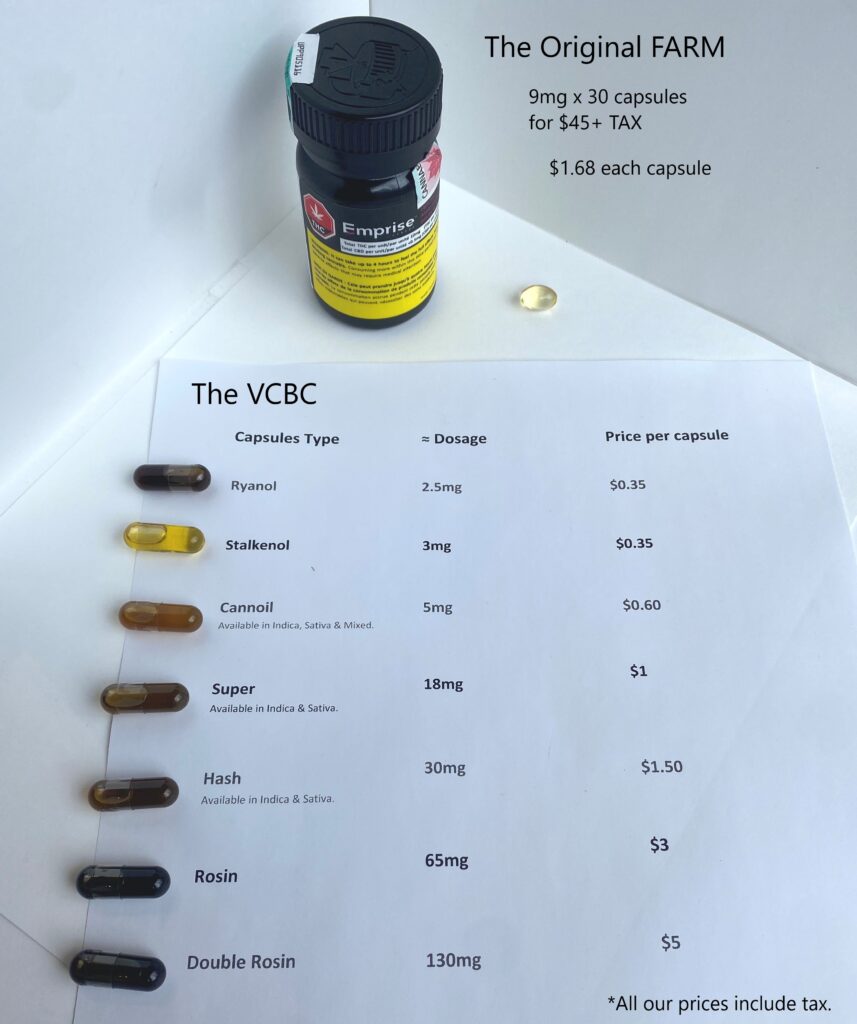

Dispensaries, most particularly Canada’s original non-profit compassion clubs, have sought to support marginalized and underserved clients with increased access to medical cannabis; the price and availability of these products has remains lower than in the retail sector, and the diversity of products, including whole-plant medicine, remains more extensive and beneficial than goods available in the recreational market.

Health Canada is in a unique position to develop an effective strategy for the provision of medicinal cannabis access and for the effective separation of the provision of medical cannabis from the recreational market. Cannabis dispensaries in Canada have a long history of providing access to patients who are unwilling or unable to access their medicine in traditional markets, and these dispensaries need our help to remain providers of this valuable and cost-saving alternative to EDH prescription medications.

References

Belackova, V., Maalsté, N., Zabransky, T., & Grund, J.P. (2015). “Should I Buy or Should I Grow?” How drug policy institutions and drug market transaction costs shape the decision to self-supply with cannabis in the Netherlands and the Czech Republic, International Journal of Drug Policy, 26, 296-310.

Bradford, A. & Bradford, W. D. (2018). The impact of medical cannabis legalization on prescription medication use and costs under Medicare part D. The Journal of Law and Economics, 61(3). 461-487.

Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction (CCSA) (2019). Canadian substance use costs and harms 2007- 2014. http://ccsa.ca

Cannabis Regulations (SOR/2018-144). https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/regulations/SOR-2018-144

Capler, R., Walsh, Z., Crosby, K., Belle-Isle, L,, Holtzman, S., Lucas, P., & Callaway, R. (2017). Are dispensaries indispensable? Patient experiences of access to cannabis from medical cannabis dispensaries in Canada, International Journal of Drug Policy, 47, 1-8.

Corroon, J.M., Mischley, L.K., & Sexton, M. (2017). Cannabis as a substitute for prescription drugs – a cross sectional study. Journal of Pain Research, 10, 989-998

Gryczynski, J, Schwartz, R. P., O’Grady, K.E. Restivo, L. Mitchell, S.G. & Jaffe, J.H. (2016). Understanding patterns of high-cost health care use across different substance user groups, Health Affairs, 35(1), 12-19. doi: 10.1337/hlthaff.2015.0618

Lew, J., Perez, T., Burwell, S. Colvin, C. Blahous, C III . . . Cohen, M. (2015). The 2015 annual report of the boards of trustees of the federal hospital insurance and federal supplementary medical insurance trust funds. https://www.cms.gov/research-statistics-data-and-systems/statistics-trends-and reports/reportstrustfunds/downloads/tr2015.pdf

Lucas, P., & Walsh, Z. (2017). Medical cannabis access, use, and substitution for prescription opioids and other substances: A survey of authorized medical cannabis patients, International Journal of Drug Policy, 42, 30- 35.

The Need for Support for Canada’s Cannabis Dispensaries

Powell, D., Pacula, R. L., & Jacobson, M. (2018). Do medical marijuana laws reduce addictions and deaths related to pain killers? Journal of Health Economics, 58, 29-42

Sen, A. (2018). Cannabis countdown: Estimating the size of illegal markets and lost tax revenue post-legalization. CD Howe Institute.

Stith, S. S., Vigil, J. M., Adams, I.M., & Reeve, A.P. (2017). Effects of legal access to cannabis on Scheduled II-V drug prescriptions. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 19(1), 59-64.