Campaign falls short, but will try again

By Judith Stamps

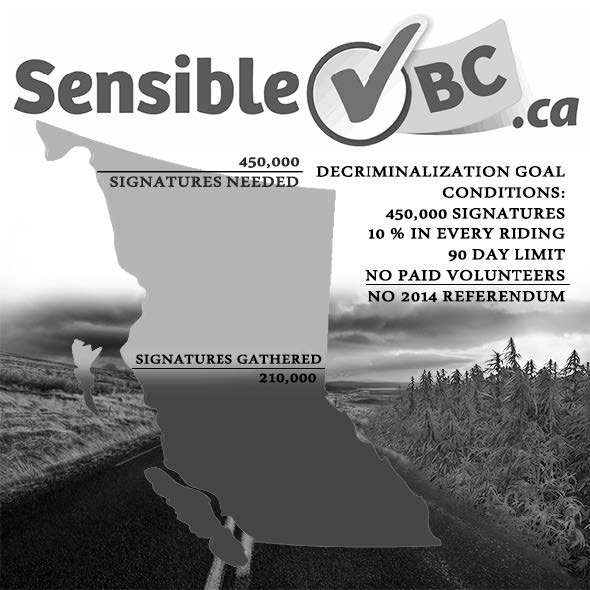

In Sept. 2013, cannabis activists in B.C. petitioned to create a future for themselves other than the one imagined for them by their federal government. While the attempt failed numerically, it succeeded in broadening the network of like-minded marijuana activists in B.C. If their work is to continue, it is worth taking a closer look at what happened.

The Sensible BC idea grew out of a series of discussions that activist Dana Larsen had with his associates at End Prohibition, a group within the Federal NDP, in the months prior to Sept. 2012. These included meetings with solicitor Kirk Tousaw. The first task was to draft legislation that would decriminalize marijuana in B.C. whilst staying within the parameters of provincial law. The result was a draft for the Sensible Policing Act, which called for police to spend their budgets solely on investigating crimes of violence or crimes with victims. The Act called, as well, for the province to apply for a federal exemption that would allow it to regulate and tax the plant.

In Sept. 2012, Larsen held a press conference to announce the campaign. The timing was good. The Union of BC Municipalities had passed a resolution in support of decriminalizing marijuana. Eight city councils around the province had endorsed ending prohibition. Following the press conference, Larsen plunged into the abyss. He conducted two solo tours, visiting 110 provincial towns in all. They were cold calls. He rented halls and placed ads in local papers announcing his time of arrival and intention to speak. Sometimes there was an audience; sometimes there wasn’t.

Meanwhile, citizens’ initiatives in Washington and Colorado to legalize marijuana for recreational use had succeeded. They were on their way. And so, it seemed, was B.C. Then manna fell from heaven. Terrace resident and marijuana enthusiast Bob Erb, won a lottery for 25 million dollars. To Sensible BC, he donated $250 thousand.

By Aug. 2013, a network was in place… sort of. During his second tour, Larsen had found volunteers who offered to act as local leaders. Most were unknown to him personally. Facebook pages were established, and some recruits were found through these. Others came through word of mouth. Few of the volunteers knew each other; even fewer had experience. Thus, by day one of the signature collection period, many ridings had coordinators, and some didn’t. Larsen had secured an office in Vancouver, staffed by a few paid organizers with NGO experience. A former HST campaign organizer was paid to oversee B.C.’s Interior and North. The CannaBus, a travelling petition booth, began touring the province. In Victoria, zone coordinator Cam Birge provided a second miracle—rent, with trimmings, for a downtown office.

Thus began the Sensible Journey, a mass—and somewhat mad—attempt to grapple with the Recall and Initiative Act (RIA) in B.C. It has to be said at the outset that this Act is in its infancy. Citizens’ initiatives—Acts that allow voters to alter existing laws—have been around in North America since the Reform Era of the late 19th century; their accompanying literature would fill a library. By contrast, B.C.’s RIA came into force only in 1995. Originally proposed in 1990 by Bill Vander Zalm, the idea was put to a referendum and approved by 83 percent of the voters. A populist, Vander Zalm favoured direct democracy. When his party lost its mandate, the provincial NDP inherited the idea and ran with it. And they wrote the rules.

By Dec. 2013, these rules had bitten the heart of every Sensible BC canvasser who had stood on a sidewalk or knocked on a door. They called for the signatures of 10 percent of the voting public in each of BC’s 85 electoral ridings, to be collected within 90 days: 400 thousand signatures for a population of 4 million. By contrast, Washington State’s formula required 250 thousand signatures for a population of 6, 900, 000. Canvassers there had six months to collect, and no distribution requirements. Further, British Columbians could use volunteer canvassers only; Washingtonians could pay them. Typically, canvassers can only petition in public spaces. In B.C., regional shopping malls were off-limits—a deadly restriction in the suburbs. In Washington State, such malls, by law, are public. In sum, their mountain was half the height of BC’s; they had twice as long to climb it; they had no distribution weight on their backs; and they could use professional climbers.

But Fight the HST had climbed the mountain in 2010. So why couldn’t Sensible BC? To collect signatures, they needed first to recruit canvassers. But there was no coherent plan. In the months prior to the real petition, “pre-petition” sheets had been circulated, inviting people to sign up as volunteers or as advocates. Similar forms could be signed online. These early events provided a database of supporters, but they confused signers. After day one, supporters unwittingly launched a campaign to drive canvassers mad. They took to rushing by signing stations with cheery smiles, shouting “I already signed online.” Then they disappeared. Soon “You can’t sign the petition online” wallpapered the Facebook pages.

The pre-petition campaign did little to bring in masses of committed canvassers. Moreover, few organizers knew how to train them. There were contradictory ideas about what canvassers needed to do. Sensible BC ads asked them to sign up sympathetic friends. Pragmatists divided “signatures required per riding” by 90 days, and realized they needed hundreds per week. The friend idea worked poorly. The pragmatic plan was more successful, but was carried out by a really small number of super canvassers. The optimists predicted exponential growth, but this occurred on paper only. Stacks of canvasser cards burst their elastic bands; alarming numbers of canvassers never picked them up. Of those that did, too few returned with signatures.

Meanwhile, riding organizers, overwhelmed by the lack of canvasser response, were hard pressed. Some gave up; some tried harder to contact their volunteers. Some joined the ranks of super canvassers and attempted, with a few helpers, to finish their ridings by themselves. Occasionally, this strategy worked. What Sensible BC needed, and never had, was a core of leaders experienced in the nuts and bolts of petitioning. Still, it must be said that Dana Larsen himself remained an inspiration. He was tenacious, patient with grumblers, and goodhearted. He answered his own phone, responding personally to messages from the far ends of the universe—even Victoria. He chatted on Facebook. He worked insanely hard.

No understanding of the campaign can be complete without a hard look at the range of public response: hostility, paranoia, and unbounded joy. Overt hostility was rare, but very annoying. At Vancouver’s Translink Stations, for example, canvassers were expelled, re-invited (our mistake) and thereafter harassed. More often, passersby simply quickened their step and spotted something to see elsewhere. Paranoia, on the other hand, was common. “I’m on your side, but I can’t afford to get on a list.” Canvassers heard it everywhere. It was the alphabet soup, the spy version: NSA, DEA, and RCMP. Then there were the signers. Some listened cautiously, and in the end convinced. Most others took one look and said, “Where’s the pen?”

For supporters, there will be more. In 2014, Larsen and Tousaw plan to launch litigation to sort out the issue of what constitutes a public space in BC. During the campaign, Sensible BC canvassers were evicted from BC Ferries terminals. They were barred from the City of Surrey, which declared itself off-limits to petitions. They received tickets issued by bylaw officers. These are matters that must be resolved, if only because there is more at stake here than a petition by Sensible BC. If British Columbians are to have any chance of success at direct democracy, they will need a place to stand.

So how did it go? Numerically, 20 of BC’s ridings achieved their 10 percent goal or better. A few more were very close. At least half got halfway there. Is this result good? Considering how few canvassers achieved it, one would have to say it is very good. In addition, much has been accomplished. A public conversation has begun—a positive one. Especially positive is that many returned to sign after reconsidering. They liked it. Moreover, the clouds are dispersing: the media has been supportive, the police have been tolerant, and supporters have grown a little bolder. A wider network of activists has been established and plans are astir for phase two. Fans, onlookers, and others should watch this space for further developments.