Judith Stamps

Last Tuesday evening, November 24 2015, I had the unique privilege of speaking at a forum on cannabis held at the Temple Emanu-El, the conservative Jewish synagogue in Victoria BC. The event was planned and hosted by the congregation’s spiritual leader, Rabbi Harry Brechner. On the panel with me were Dieter MacPherson, president and executive director of Victoria’s oldest compassion club, the Victoria Cannabis Buyers’ Club, and Dr. Arnold Schoichet, one of a small percentage of BC’s 12,000 physicians willing to provide patients with a recommendation for cannabis. Moderating the panel and the ensuing group discussion was congregation member Richard Kool, associate professor of environmental studies at Victoria’s Royal Roads University.

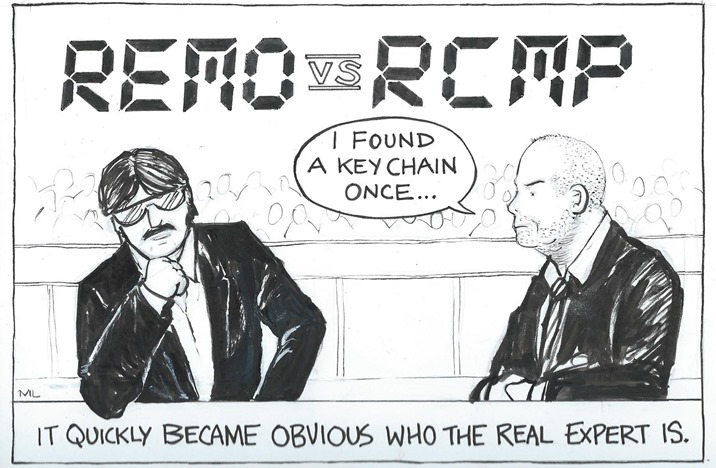

Each of the panelists gave a short talk: I, on the history and roots of cannabis prohibition in North America; Dieter on dispensaries and the process of regulation; Arnold on how he came to be a cannabis doctor. On myself, and on Dieter, I will say little. I began working with Dana Larsen and Sensible BC, and with local activist, Ted Smith in 2013. Dieter, erstwhile grower, is Victoria’s resident expert and preferred spokesperson on all things medical cannabis. Arnold is a family physician who moved from practicing obstetrics to establishing a cannabis friendly clinic in Mission BC, all at the behest of his longtime friend John Conroy, an activist lawyer well known in these parts. Rabbi Harry ended the evening with a reading on how cannabis might fit into Judaic law, and it is on this reading that I will focus today.

Allow me to begin by saying that this forum is one of the first, if not actually the first, Canadian cannabis forum put on by a religious leader for his/her congregation. It was an historic event. On medical use the Rabbi had this to say. Judaic law centres on the concept of the “mitzvah,” a commandment of God, also roughly translated as a good deed. One of the commandments is to care for the body, and where needed, 1observed, shares an etymological root with the word ‘whole.’ To heal is thus to make whole. According to my Webster’s Third New International Dictionary, the root is the Middle English ‘hellen,’ and the Old High German, ‘heilen.’ I will take this discussion a step farther, and note two other words based on this root: ‘holy,’ meaning sacred; and ‘hail,’ meaning acclaim, as in ‘hail to the chief,’ or summon, as in ‘to hail a cab.’ Needless to say, but I’ll say it anyway, ‘hellen/heilen’ is also the root of ‘hale,’ and in ‘hale and hardy,’ and ‘health,’ as in Health Canada. New Minister of Health, Jane Philpott, please take note. We’ve been torn asunder for far too long, and wish to be made whole.

Allow me to begin by saying that this forum is one of the first, if not actually the first, Canadian cannabis forum put on by a religious leader for his/her congregation. It was an historic event. On medical use the Rabbi had this to say. Judaic law centres on the concept of the “mitzvah,” a commandment of God, also roughly translated as a good deed. One of the commandments is to care for the body, and where needed, 1observed, shares an etymological root with the word ‘whole.’ To heal is thus to make whole. According to my Webster’s Third New International Dictionary, the root is the Middle English ‘hellen,’ and the Old High German, ‘heilen.’ I will take this discussion a step farther, and note two other words based on this root: ‘holy,’ meaning sacred; and ‘hail,’ meaning acclaim, as in ‘hail to the chief,’ or summon, as in ‘to hail a cab.’ Needless to say, but I’ll say it anyway, ‘hellen/heilen’ is also the root of ‘hale,’ and in ‘hale and hardy,’ and ‘health,’ as in Health Canada. New Minister of Health, Jane Philpott, please take note. We’ve been torn asunder for far too long, and wish to be made whole.

As we are in symbiosis with the plant world, it is only fitting that consuming plants found to be nutritious or healing should make us whole. Most of our medicines come from plants. They are a gift from God. It would be a transgression not to use a plant where it could heal, and a mitzvah to use it in this manner.

Lately I have been attending, or viewing on You Tube, a number of cannabis forums. I shall make note that very little is said at these events on the spiritual uses of this plant, if they are mentioned at all. On Tuesday evening, Rabbi Harry brought to our attention the word, ‘kaneh-bosm,’ found in the Hebrew Bible, in the Book of Exodus. According to the story of exodus kaneh-bosm was a key ingredient in the anointing oil used in that day. Some historians believe that kaneh-bosm is an ancient term for cannabis. This belief, I add, is traceable to the work of Sula Benet (1903-1982), a polish-born anthropologist, who did extensive, comparative linguistic analysis of ancient middle-eastern languages. BC cannabis historian and activist, Chris Bennett, supports her view, and others have followed. Is kaneh-bosm really cannabis, asks the Rabbi? Who knows? It could be. The theory is intriguing In any case, it is certain that the plant has ancient usages. Hashish is associated in legend with the Middle East. The earliest formularies that list cannabis as a medicine date from 1000 BC, and it is an age-old tradition to make cannabis infusions for religious festivals in India.

Lately I have been attending, or viewing on You Tube, a number of cannabis forums. I shall make note that very little is said at these events on the spiritual uses of this plant, if they are mentioned at all. On Tuesday evening, Rabbi Harry brought to our attention the word, ‘kaneh-bosm,’ found in the Hebrew Bible, in the Book of Exodus. According to the story of exodus kaneh-bosm was a key ingredient in the anointing oil used in that day. Some historians believe that kaneh-bosm is an ancient term for cannabis. This belief, I add, is traceable to the work of Sula Benet (1903-1982), a polish-born anthropologist, who did extensive, comparative linguistic analysis of ancient middle-eastern languages. BC cannabis historian and activist, Chris Bennett, supports her view, and others have followed. Is kaneh-bosm really cannabis, asks the Rabbi? Who knows? It could be. The theory is intriguing In any case, it is certain that the plant has ancient usages. Hashish is associated in legend with the Middle East. The earliest formularies that list cannabis as a medicine date from 1000 BC, and it is an age-old tradition to make cannabis infusions for religious festivals in India.

What then about recreational use? In Jewish culture it is standard practice to use wine for encouraging and enhancing joy. On the Sabbath, for example, one drinks wine to inspire group singing and dancing, and ultimately, if one is a mystic, to induce ecstatic feeling. To create such feeling is a mitzvah. On this topic the Rabbi made two points, both profound.

Wine, he observed, has a traditional, ritualistic place both in Jewish culture, and in the West generally. It accompanies our rites of passage: we serve it at weddings, anniversaries, birth ceremonies, coming of age ceremonies, funerals, and on all other special days. There are, in addition, standard blessings for wine. These elements create a social and spiritual structure in which wine takes a prescribed place in our lives. The structure sanctions the substance, but also provides guidelines for use: under what circumstances to imbibe, how much to take, and so on. In this gentle manner it teaches limits. One of the more insidious consequences of prohibition is the erasure of social memory. After three and a half generations of shrill, anti-cannabis propaganda most North Americans have no recollection of its traditional place as a medicine, and know almost nothing of its customary religious and social uses. In Canada’s early post legalization years, the journals of novice, raised-with-alcohol cannabis fans, will be first hand records of how it feels to lack this kind of ritual.

Being torn from custom can have devastating effects. In his work, The Omnivore’s Dilemma, historian Michael Pollan points out that North Americans lack deeply rooted food customs. Well-established local cuisines have stabilizing effects. Without them we are vulnerable, easily blown off course by food fads, favourite instruments of the food industry. What, then, will structure our cannabis use? Rituals are evolutionary things; they cannot be invented in short order. Three levels of government will regulate where cannabis is to be sold and consumed, how it is to be taxed, and who is to participate in the industry. But how will we develop good traditions for use that we can pass onto our children? Will we, as a society, find the activities to which cannabis is best suited? Will we learn to employ it in the spirit of rendering ourselves whole, holy, socially healed?

Being torn from custom can have devastating effects. In his work, The Omnivore’s Dilemma, historian Michael Pollan points out that North Americans lack deeply rooted food customs. Well-established local cuisines have stabilizing effects. Without them we are vulnerable, easily blown off course by food fads, favourite instruments of the food industry. What, then, will structure our cannabis use? Rituals are evolutionary things; they cannot be invented in short order. Three levels of government will regulate where cannabis is to be sold and consumed, how it is to be taxed, and who is to participate in the industry. But how will we develop good traditions for use that we can pass onto our children? Will we, as a society, find the activities to which cannabis is best suited? Will we learn to employ it in the spirit of rendering ourselves whole, holy, socially healed?

These last thoughts are germane to the Rabbi’s second point. It is not correct, he argued, to think of recreational cannabis use as trivial, or escapist. Unique to cannabis—compared to wine, spirits, tobacco, coffee, and other currently legal plant derivatives—is its ability to shift our perspective on the world. Through its effects we can come to see our lives, our problems, and those of others in new and helpful ways. This is a vital point, to be repeated daily. Here’s my take on it. Suppose you take cannabis when you are troubled or confused. Under its influence, you gaze at your troubles from a new breed of distance, yielding a new species of objectivity. You engage in some useful analysis, and sort out a few strategies for improving your circumstances. After that, life gets better. Of course you will also want take cannabis on occasions when you are feeling fine. When you do that you will likely find yourself contemplating special relativity, string theory, or fractal patterns in nature. Cannabis is a thinking person’s plant. I venture to say, that is why the hard political right rejects it. More generally, cannabis is unique among the hallucinogens for its tendency, in a mild way, to encourage its fans to look inward. For this reason, it will not appeal to everyone. If you like drinking in order to numb yourself, you will find this plant a bad substitute. If you drink too much, and plan to stop drinking, however, you will find it useful

The Rabbi moved from this discussion to the question: what is it about cannabis that we are we so afraid of? It was a rhetorical question. Still, it is important remind ourselves that, as a society, we have been taught to think of cannabis as a contaminant. From 2013 until last October, the Harper government alone spent eleven plus million dollars telling Canadian parents that cannabis could rob their children of intelligence, and even of sanity. That’s quite a threat. The first US state cannabis prohibitions date from around 1915. For a hundred years, cannabis has been associated the criminal, the insane, the degenerate, and the just plain disgusting. We don’t want to be labeled any of those things.

The Rabbi moved from this discussion to the question: what is it about cannabis that we are we so afraid of? It was a rhetorical question. Still, it is important remind ourselves that, as a society, we have been taught to think of cannabis as a contaminant. From 2013 until last October, the Harper government alone spent eleven plus million dollars telling Canadian parents that cannabis could rob their children of intelligence, and even of sanity. That’s quite a threat. The first US state cannabis prohibitions date from around 1915. For a hundred years, cannabis has been associated the criminal, the insane, the degenerate, and the just plain disgusting. We don’t want to be labeled any of those things.

Tuesday’s forum ended with a story, soon to become Jewish legend. In recent weeks Rabbi Harry had been conducting a bit of his own research on cannabis, and had attempted to do a Kabbalistic, or numerological reading on ‘420.’ Numerology, a mystical practice favoured by some Jewish groups, associates letters of the alphabet with numbers. Each given word or name can be translated into a number. Some numbers are thought to be especially propitious. Working backward, said Harry, he had found that the number ‘420’ yielded the word, ‘smoke,’ a good sign, he added. As you can well imagine, this story cheered us immensely, and was greeted with peals of laughter. I haven’t a clue on numerology. Is this a true story? A revelation? A hypnotic suggestion, perhaps? Who cares? It is enough that the Rabbi told it.

It is enough too, that Congregation Emanu-El’s spiritual leader chose to lead in helping us come to terms with the future. It can only be hoped that others follow suit. Legalization, at this stage, has many precedents. We can pick a fair model, go for it, and expect reasonable success. A fair cultural transformation, by contrast, is generations away. For that we need all the help we can get.