The Good

In a comprehensive final report by the Task Force on Cannabis Legalization and Regulation, released to the public on Tues Dec 13, 2016, recommendations covering a broad range of areas of public policy have attempted to nurture the development of a robust industry, while addressing potential problems. Some recommendations appear very favourable to established cannabis advocates, while others are far too restrictive and bound to be struck down in court.

Overall, these proposed regulations are a positive step forward and will give the federal government a solid base upon which to frame the actual laws, which are expected to be introduced Parliament in the spring of 2017.

Overall, these proposed regulations are a positive step forward and will give the federal government a solid base upon which to frame the actual laws, which are expected to be introduced Parliament in the spring of 2017.

With so many opposing forces demanding extreme positions, it was impossible for the task force to please everyone and this document seems to be a genuine attempt to strike a balance between conservative parents and a free society. Acknowledging this report as a beginning framework upon which to regulate cannabis, the task force has done a decent job setting the stage, though there are some serious flaws that will no doubt be improved upon over time. For now advocates have their work cut out for them to make sure those improvements happen sooner than later.

Clearly, this is a historical moment for our country. In the foreword the task force touches upon the monumental shift that is occurring.

“For millennia, people have found ways to interact with cannabis for a range of medical, industrial, spiritual and social reasons, and modern science is only just beginning to unpack the intricacies of cannabinoid pharmacology. We are now shaping a new phase in this relationship and, as we do so, we recognize our stewardship not just of this unique plant but also of our fragile environment, our social and corporate responsibilities, and our health and humanity.”

Here is my brief synopsis of this report. I give you the Good, the Bad and the Ugly.

The Good: Allowing provinces to determine distribution systems and encouraging intensive consultation with municipalities bodes well for established dispensaries in cities that have started to issue licenses to them. Suggesting that the security requirements for become a Licensed Producers need to be reduced so as to allow for smaller craft growers, there even appears to be hope that the current suppliers of dispensaries could also merge into the new legal system.

In the Introduction, the task force makes it clear not everyone involved in the cannabis industry is in it for money. “A network of cannabis growers, consumers and advocates who engage in an underground economy of cannabis cultivation and sale for compassionate reasons also exists. While these activities are in violation of the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act (CDSA), some cannabis stores (“dispensaries”) and wellness clinics (“compassion clubs”) have nevertheless been in operation for many years in parts of the country. The Task Force heard from several members of, and advocates for, this community who report developing and adhering to a strict internal code of standards, closely resembling self-regulation, and who wish to differentiate themselves from solely profit-driven, illicit enterprises.”

In the Introduction, the task force makes it clear not everyone involved in the cannabis industry is in it for money. “A network of cannabis growers, consumers and advocates who engage in an underground economy of cannabis cultivation and sale for compassionate reasons also exists. While these activities are in violation of the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act (CDSA), some cannabis stores (“dispensaries”) and wellness clinics (“compassion clubs”) have nevertheless been in operation for many years in parts of the country. The Task Force heard from several members of, and advocates for, this community who report developing and adhering to a strict internal code of standards, closely resembling self-regulation, and who wish to differentiate themselves from solely profit-driven, illicit enterprises.”

In Chapter 2, Minimizing Harms of Use, they go further, to say, “At the same time, the framework should reconsider existing security requirements that are in place under the Access to Cannabis for Medical Purposes Regulations. We acknowledge that security requirements should not be so strict that they are prohibitively expensive or difficult to implement, thus creating unnecessary barriers to entry into the regulated marketplace.”

In an interview with the Times Colonist, Victoria Mayor Lisa Helps said once the province takes over regulation of marijuana distribution, the city will likely scrap its cannabis bylaws. “That way we’ll have a comprehensive approach across the province, not one jurisdiction to one jurisdiction,” Helps said. “Our regulations were meant to fill a vacuum. We were waiting for the federal government to show leadership.”

Setting the minimum age at 18 was an unexpected surprise, especially given the pressure the Canadian Medical Association applied to have the limit set at 25. In the second chapter the task force explains their wisdom in this decision.

Setting the minimum age at 18 was an unexpected surprise, especially given the pressure the Canadian Medical Association applied to have the limit set at 25. In the second chapter the task force explains their wisdom in this decision.

“Research suggests that cannabis use during adolescence may be associated with effects on the development of the brain. Use before a certain age comes with increased risk. Yet current science is not definitive on a safe age for cannabis use, so science alone cannot be relied upon to determine the age of lawful purchase.

Recognizing that persons under the age of 25 represent the segment of the population most likely to consume cannabis and to be charged with a cannabis possession offence, and in view of the Government’s intention to move away from a system that criminalizes the use of cannabis, it is important in setting a minimum age that we do not disadvantage this population.

There was broad agreement among participants and the Task Force that setting the bar for legal access too high could result in a range of unintended consequences, such as leading those consumers to continue to purchase cannabis on the illicit market.

For these reasons, the Task Force is of the view that the federal government should set a minimum age of 18 for the legal sale of cannabis, leaving it to provinces and territories to set a higher minimum age should they wish to do so.”

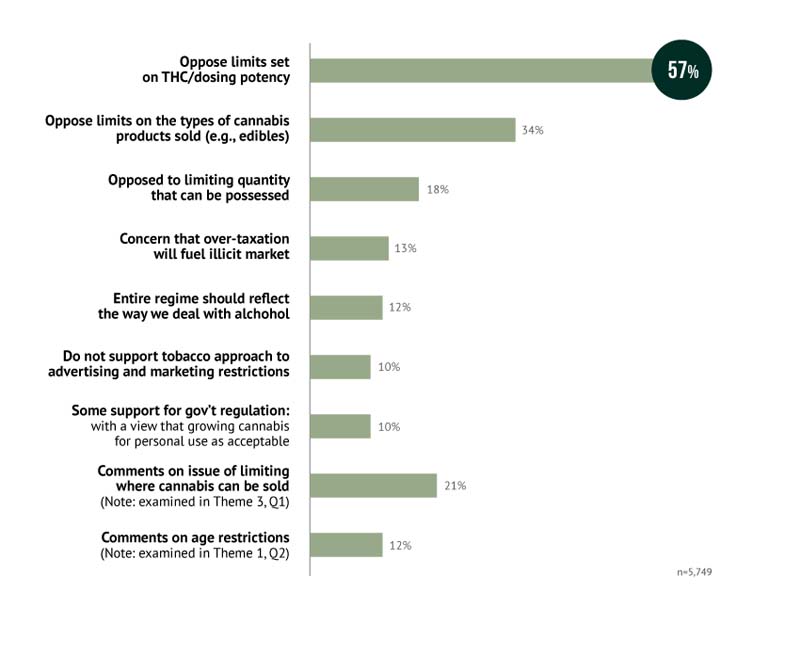

Another pleasant surprise came when the task force refused to place limits on THC content or try to stop edible cannabis products from entering the market, as the city of Vancouver has done in its licensing of dispensaries. With so many fear mongers out there, it seemed unlikely the task force would have such an open position but in chapter 2 they do their best to explain why THC limits and similar measures would have counter-productive impacts.

Another pleasant surprise came when the task force refused to place limits on THC content or try to stop edible cannabis products from entering the market, as the city of Vancouver has done in its licensing of dispensaries. With so many fear mongers out there, it seemed unlikely the task force would have such an open position but in chapter 2 they do their best to explain why THC limits and similar measures would have counter-productive impacts.

“In weighing the arguments for and against limitations on edibles, the majority of the Task Force concluded that allowing these products offers an opportunity to better address other health risks. Edible cannabis products offer the possibility of shifting consumers away from smoked cannabis and any associated lung-related harms. This is of benefit not just to the user but also to those around them who would otherwise be subject to second-hand smoke.

This position comes with caveats. To protect the most vulnerable, any products that are “appealing to children,” such as candies and other sweets, should be prohibited. We acknowledge that there is considerable discretion in what constitutes “appealing to children.”

…While there may be risks of consuming high-potency concentrates, the dangers inherent in their production strongly suggest that they be included as a part of the regulated industry, subject to effective safety and quality-control restrictions. The harms associated with high THC potency remain a concern, and should be minimized. However, we do not believe that limiting THC content in concentrates is the most effective way to do so, based on current information. We agree that, due to a lack of evidence, any chosen threshold would be arbitrary and a challenge to enforce. Even the standard THC content of today’s dried cannabis is considered high by historical standards.”

Instead of creating arbitrary limits, the task force wants the government to use taxes to curb excessive use of potent cannabis products, as also outlined in chapter 2. “We suggest that variable tax rates or minimum prices linked to THC level (potency), similar to the pricing models used by several provinces and territories for beer, wine and spirits, should be applied to encourage consumers to purchase less-potent products.”

As for advertising, it seem the proposals are relatively fair, though likely to change over time as the public loses its fear of the herb. Details on permitted advertising are also in chapter 2, and are very similar to how advertising for alcohol and tobacco are managed.

“Comprehensive advertising restrictions should cover any medium, including print, broadcast, social media, branded merchandise, etc., and should apply to all cannabis products, including related accessories. Such restrictions could still leave room for promotion at the point of sale, which would answer industry concerns about allowing information to be provided to consumers and some branding to differentiate their products from the illicit market and other producers.”

Next blog we get to the bad.