Judith Stamps

Some authors weave their chronicles into geometric shapes, presenting history as a long, upward trudge toward progress, usually via reason, and science; or portraying it as the steady, moral and physical decline of humanity from a nobler past; or showing a never ending round, as Mark Twain liked to say, of ‘one damned thing after another.’ Each shape is based in a grand system of belief. Still other historical accounts offer sustained arguments for particular theories. The best example in cannabis history is Jack Herer’s 1985 publication, The Emperor Wears No Clothes, wherein the author argues that, having seen that hemp would compete too well with their own products, Dupont, along with press baron, William Randolf Hearst, with interests in the lumber business, conspired successfully to have it banned.

Larsen’s history, Cannabis in Canada, is none of the above. He offers no overarching geometry, and no grand theory of conspiracy. This quality is good. It means that, as histories go, Cannabis in Canada is not ideologically driven. Rather, it offers a fact filled account of Canada’s relation to industrial hemp dating from the mid 17th century, and to medical cannabis dating from the mid 19th century. If there is an overall message it is this. Industrial hemp was legal north of the 49th parallel from 1650 to 1938, during World War II, and again from the mid 1990s onward. That gives us about 350 years of legal Canadian hemp. Medical cannabis medicine was legal from 1850 until some point in the 1930s; and became at least technically legal again 1998, and more functionally so after 2000. That’s over 100 years of legal medical cannabis. Prohibition, by contrast, has been with us for around 70 years. So legal hemp, and legal cannabis medicine are, in fact, Canada’s ‘normal.’ And it is prohibition that represents the abnormal.

Cannabis in Canada highlights the international rivalry, during the mercantile era, for growing or acquiring the best hemp fibre for rope and sails. It portrays the racist roots of Canada’s recreational drug laws, and the absurdly opaque process by which, in 1923, cannabis became illegal in Canada. It chronicles the reefer madness era, overseen by Col. Sharman in Canada, and Harry Anslinger in the US, and the movements, from the 1960s onward, to legalize the plant. Larsen introduces readers to some of the key activists in Canada, and to the legal battles that have brought us to the point of ‘almost legalization’ today.

In addition to these historical records, Cannabis in Canada offers technical information on industrial hemp, and on the wildly diverse uses to which it can be put. It covers cannabis as medicine, offering basics on cannabinoids, on the body’s system of cannabinoid receptors, and on the development of cannabis science. Alongside these, we learn the story of the rise of medical cannabis dispensaries in North America from 1996 inward.

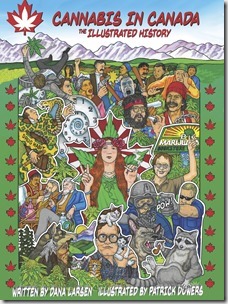

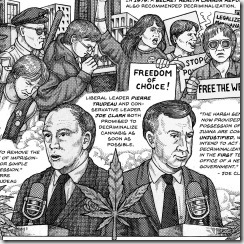

As its title suggests, Cannabis in Canada is illustrated. Each of its 140 pages bears an elaborate drawing, and sometimes a collage of ads, posters, and photos, done by artist, Patrick Dowers, into which the text is set. As such, it follows in the footsteps of 1930s comic artist, Will Eisener, and a long line of authors who now work in the genre for both fiction and non-fiction texts. Dower’s black and white ink drawings and montages are finely detailed, and mildly cartoony, with a primitive edge. They’re busy, imaginative, charming, and just plain fun.

As its title suggests, Cannabis in Canada is illustrated. Each of its 140 pages bears an elaborate drawing, and sometimes a collage of ads, posters, and photos, done by artist, Patrick Dowers, into which the text is set. As such, it follows in the footsteps of 1930s comic artist, Will Eisener, and a long line of authors who now work in the genre for both fiction and non-fiction texts. Dower’s black and white ink drawings and montages are finely detailed, and mildly cartoony, with a primitive edge. They’re busy, imaginative, charming, and just plain fun.

I have only two quarrels with Cannabis in Canada. On occasion, Larsen adopts an historical argument that is contentious, but without indicating this fact to the reader. For example, he describes the British blockade of European trade during the Napoleonic wars, and Napoleon’s response to it, as centred mainly on the international need to obtain hemp fibre. Here Larsen follows the analysis offered earlier by Jack Herer. The standard procedure for historians is to describe a set of events, explain how others have interpreted them, and then tell the reader what evidence would suggest that the historian’s new interpretation is superior. Neither author lists alternative interpretations of these events, or even indicates that there might be some. There were many products on offer during the industrial revolution. It is at least possible that in 1806, cannabis was less central to that war than the Herer/Larsen theory suggests.

I would also like to have seen a more standard, usable approach to the book’s references. Larsen’s reference pages are a series of code numbers, divided into chapters. Directions on the first page instruct the reader to go to the cannabis history website, and enter the desired codes. I tried to get the first reference in Chapter two, labeled “2-1.” It is supposed to tell us about protein levels in cannabis. 2-1, however, leads the reader to a lengthy PDF of a Philippe Lucas article, which one has to download. I did so, but a search using the word ‘protein’ didn’t turn up anything. I wasn’t about to read it all, and readers should not need to traipse through so much procedure just to find a point. The reference section, in my view, is not user friendly. The standard history text reference offers the name of its author, the title of her or his publication, and the page number on which the reference can be found. Some of us do like to read the references, and we need that kind of precision to access them. Besides this, the opportunity to glance at the standard reference page allows readers to see immediately what studies the book’s author has been reading. Lists of chapter numbers and code numbers tell us nothing of the sort. It would have been nice, too, to see a page or two of select bibliography.

Overall I have no doubt that Cannabis in Canada will earn the respect of readers who delve into it. As the book’s editor, I would have liked to see it brought out by a Canadian or BC publisher, but as I never attempted to do the legwork on that project, I am in a weak position to complain. Still, a more official publication would have garnered some media reviews, and these are helpful. Big Media does not review self-published books. Similarly, I was mildly disappointed to see the ads in this book. Whilst I have no quarrel with ads as such, ads for cannabis products are not yet legal in Canada. So on a practical level, this book would be difficult for Canadian bookstore owners to carry. Cannabis in Canada is a well-done, interesting read. Some thought needs to be given now to distribution beyond the activist community.