(image : The Night Dad Went to Jail)

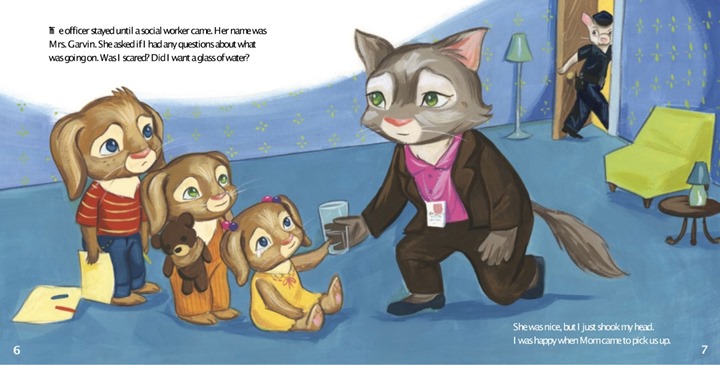

Cannabis and the Young Brain: Prohibition’s Forgotten Victims

Listen to Rona Ambrose, Canada’s Health Minister, or Nora Volkow, America’s Director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, and you will soon conclude that cannabis prohibition today rests on a single, nearly unassailable platform: it is bad for youth. As expressed today, this claim is based on research published in the Journal of Neuroscience in April 2014. Researchers looked at brain differences in 40 young people: 20 who had, and 20 had not been ‘smoking marijuana.’ The scans in the first group showed ‘abnormalities’ in the amygdala and nucleus accumbens, brain areas associated with emotion, memory, decision-making and motivation. Scans are not self-interpreting, and scientific interpreters have yet to determine what these particular results mean. Meanwhile the articles have spawned concern, and a bit too much policy.

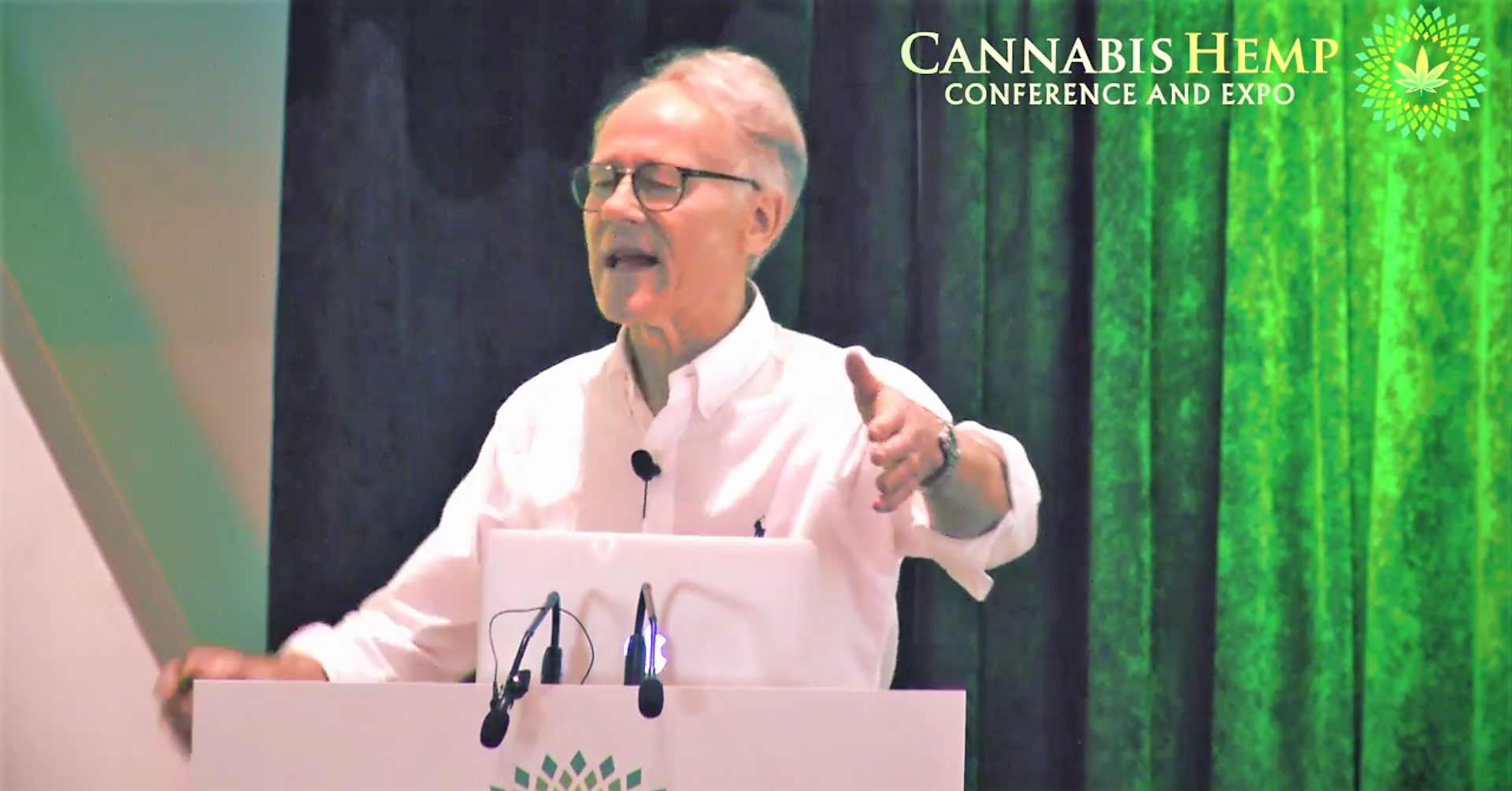

Whether out of similar concern or for other reasons, activists in nations, states and towns now regulating cannabis agree universally that recreational use is suitable only for adults. They argue, with good sense, that youth are better protected where cannabis is regulated, and not left to the black market. Rona Ambrose is fond of quoting a 2009 UNICEF study that cites high levels of cannabis use by Canadian youth—28%. She wants that number to come down, or so she says. Serious observers of drug policy point out that where cannabis has been at least decriminalized—Germany, Italy, Spain, Portugal, California, and so on— youth participation is a fraction of Canada’s. Yet when put to Health Canada or NIDA, these points have little impact. Neither institution listens to activists.

Still, should you have the opportunity to address them, or anyone like them, here are a few talking points not to be missed.

Science is powerful, but its focus is narrow. The same can be said of politicians who like to quote scientific publications. Consider this, for example. The brain research noted above shines a spotlight on young people who appear entirely to have escaped the harsher consequences of prohibition. For those who did the brain research, such a narrow focus may do, but for political leaders and carvers of drug policy, it is unacceptable. Focusing on the brains of lucky teens, then writing policy based chiefly on that focus, leaves young victims of prohibition in the shadows, and the rest of us in a state of ignorance. Bring them out of the shadows, and you encounter young people like the following.

1. Those Who Have Been Arrested.

In 2006, 4,700 Canadians aged 12-17 were charged with a cannabis offense. In 2011, in California alone, that figure was 5,831. Multiply these figures by 10 to represent a decade, and the charges number in the tens of thousands. Arrests bring chaos to young lives. They traumatize families. They can result in parents and relatives shelling out bundles on legal representation and fees; in teens being expelled from school, or dropping out of school; in loss of friends and perhaps the good will of neighbours; in sleepless nights and anxious days that drag on for weeks. Arrests can bring depression. At best they leave young people with terrible memories.

In 2006, 4,700 Canadians aged 12-17 were charged with a cannabis offense. In 2011, in California alone, that figure was 5,831. Multiply these figures by 10 to represent a decade, and the charges number in the tens of thousands. Arrests bring chaos to young lives. They traumatize families. They can result in parents and relatives shelling out bundles on legal representation and fees; in teens being expelled from school, or dropping out of school; in loss of friends and perhaps the good will of neighbours; in sleepless nights and anxious days that drag on for weeks. Arrests can bring depression. At best they leave young people with terrible memories.

Up to 50,000 young Canadians over the past decade have gone through this kind of shredder; tens of thousands more in the US. What if someone had conducted brain scans on them before and after such arrests, before and after their long-term consequences? Might they not have revealed abnormalities? And what about black youth in the US, far more likely than whites to be arrested for the same activity? In some cities, such arrests cause entire families to be tossed out of their lodgings. What if someone had sent researchers out to find them, interview them, and tell their stories? What would we have learned? No meaningful debate on cannabis can proceed without this kind of information. Indeed, until such questions form a part of every debate on cannabis and brain research, youth arrested for cannabis remain, for all practical purposes, prohibition’s invisible, sacrificial lambs.

You’ll never hear this from Rona Ambrose, but the researchers who produced the UNICEF study that she likes to quote, understood this fact. “Legal sanctions against young people,” they wrote, “generally lead to even worse outcomes, not an improvement in their lives.” Accordingly, they recommended adopting public education programs like the ones that have already succeeded in reducing teen tobacco use.

2. Those Who Have Seen Their Home Life Shredded.

Every year children are removed from their parents’ care for reasons related to cannabis. The parents are medical users and someone objects, or they are growing plants, and someone objects, or the kids speak up in school during a drug education program, and someone objects. In the US, Keith Stroup notes, NORML gets 3 or 4 phone calls a week from distressed parents separated from children. According to criminology professor Susan Boyd, in 2005, in BC alone 40 children whose parents were growing cannabis were seized from homes. What if someone had scanned the children’s brains before and after these events? What brain areas would be affected, and with what results? Wouldn’t the effects be permanent?

Every year children are removed from their parents’ care for reasons related to cannabis. The parents are medical users and someone objects, or they are growing plants, and someone objects, or the kids speak up in school during a drug education program, and someone objects. In the US, Keith Stroup notes, NORML gets 3 or 4 phone calls a week from distressed parents separated from children. According to criminology professor Susan Boyd, in 2005, in BC alone 40 children whose parents were growing cannabis were seized from homes. What if someone had scanned the children’s brains before and after these events? What brain areas would be affected, and with what results? Wouldn’t the effects be permanent?

Every year parents are arrested, convicted and incarcerated, leaving families fatherless (most often) or motherless. Families lose key breadwinners and drift into poverty. Children’s hearts are broken, perhaps irreparably. What if we scanned their brains before and after dad was packed off to jail? Before they lost their home? Would we see the abnormalities that now place them at greater risk for depression and suicide?

And what about the children subjected to DARE, the prohibitionist school program still running in far too many places? Law enforcement officers who teach these programs encourage youth to report on friends, family and anyone else, should they see signs of ‘drug abuse.’ These practices place young people in a bind. What happens to young brains when they are forced to make choices of this kind? What if we were to scan them before and after such programs?

3. Those Who Have Survived Military Style Raids

President Reagan’s version of the war on drugs, waged in the 1980s, entailed training city police in military tactics; giving them equipment to match: armoured vehicles, M-16s, bayonets, flash-bang grenades, drones, and helicopters; and permission to conduct ‘no-knock’ paramilitary style, SWAT Team raids. Canadians have been spared these. The helicopters are used to hover over a property, allowing law enforcers to repel to the ground, smash down doors and toss in grenades. The favoured time of day for such events is 3 am, or thereabouts.

President Reagan’s version of the war on drugs, waged in the 1980s, entailed training city police in military tactics; giving them equipment to match: armoured vehicles, M-16s, bayonets, flash-bang grenades, drones, and helicopters; and permission to conduct ‘no-knock’ paramilitary style, SWAT Team raids. Canadians have been spared these. The helicopters are used to hover over a property, allowing law enforcers to repel to the ground, smash down doors and toss in grenades. The favoured time of day for such events is 3 am, or thereabouts.

During these raids family members are made to lie facedown on the floor, with guns held to their heads. In September of 2000, a California family, parents and three children, fell victim to this practice. The officer holding a gun to the head of the 11 year old had a mishap. His gun went off, killing the child instantly. There were no drugs found in the home. The family was awarded $3,000,000 in a lawsuit. The other two children are likely still to be alive.

These are not isolated events. Paramilitary drug raids in the US numbered 3,000 in 1980; 30,000 in 1995; and 45,000 in 2001. Some 10% of the time, as in the story noted above, teams raid the wrong house. How many young people have been touched by these practices? What if someone had scanned their brains before and after these raids? Wouldn’t they reveal signs of damage? And where are these young people today? Shouldn’t NIDA, the DEA and the National Institutes of Health be out there counting them?

The truth is, raids and their young victims have yet to form part of the North American psyche. Mainstream films don’t portray them; mainstream journalists don’t seek them out. No one sees them. Our regulatory institutions seem not to see them either.

4. Young people whose Brains Need Medicinal Cannabis

Every day across North America parents of children with epilepsy teach themselves, and each other how to use the cannabinoids, CBD, THC, THCV, and THCa, to reduce, and sometimes even stop, seizures. They communicate through Facebook pages, seeking and offering practical advice. In Canada whole plant extracts have become legal; Canadian parents are free to test out strains and cannabinoid ratios. In a few US States, parents are similarly free to use whatever works. In other states, children suffer more seizures because state laws are too restrictive: they allow CBD only, and CBD is not sufficient for everyone. The most unfortunate children live in states with no legal access to this medicine. Some have died. Far too many of the parents face criticism of their efforts from ‘experts’ with no remedies to offer. Critics’ time would be better spent tallying the number of young brains that might have been saved had Canada and the US legalized cannabis in the 1970s.

Every day across North America parents of children with epilepsy teach themselves, and each other how to use the cannabinoids, CBD, THC, THCV, and THCa, to reduce, and sometimes even stop, seizures. They communicate through Facebook pages, seeking and offering practical advice. In Canada whole plant extracts have become legal; Canadian parents are free to test out strains and cannabinoid ratios. In a few US States, parents are similarly free to use whatever works. In other states, children suffer more seizures because state laws are too restrictive: they allow CBD only, and CBD is not sufficient for everyone. The most unfortunate children live in states with no legal access to this medicine. Some have died. Far too many of the parents face criticism of their efforts from ‘experts’ with no remedies to offer. Critics’ time would be better spent tallying the number of young brains that might have been saved had Canada and the US legalized cannabis in the 1970s.

I end the blog today with two mental images. The first is captioned: This is your brain on cannabis; the second: This is your brain on prohibition. Brain research is a fine thing, no doubt. But it will never help us to balance these images. For that we need cannabis activists. They’re the ones who have learned to keep them in mind simultaneously.

Read more from Judith Stamps on the CD Blog