A Prologue to Reasonable Regulations for Cannabis, If Such Things Can Exist

By Judith Stamps

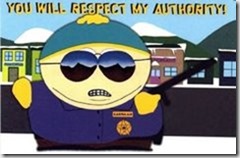

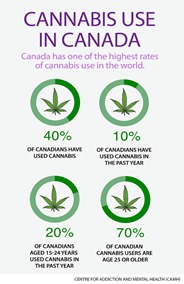

On Sunday, July 19, 2015, Conscious Living Network, a volunteer-based society in Vancouver BC, hosted its first Cannabis Conference. The panel on cannabis policy was mildly polarized: activist Marc Emery expressed the view that there should be no regulations for cannabis at all. All others took a moderate approach; public health theorist Mark Haden put the matter in perspective. Ours is a regulatory world, he noted; we regulate everything from broccoli to bicycles. The following thoughts are spin-offs of that conversation.

1. WHAT ARE REGULATIONS?

Regulations are limits on personal freedom imposed by governments or, in small communities, recognized councils. They attempt to shape our conduct, in the case of cannabis, around growing, selling, preparing, possessing, sharing and partaking. They define options, or at least they try to. They manipulate incentives; easing paths by providing tax relief, or relaxing building codes; or blocking paths by denying the above, and more besides.

Regulations are limits on personal freedom imposed by governments or, in small communities, recognized councils. They attempt to shape our conduct, in the case of cannabis, around growing, selling, preparing, possessing, sharing and partaking. They define options, or at least they try to. They manipulate incentives; easing paths by providing tax relief, or relaxing building codes; or blocking paths by denying the above, and more besides.

Regulations are the signposts of an imperfect reality. English food regulations dating from the 13th century aimed to stop the practice of watering down beer and wine. Canada’s first attempt was the 1875 Act to Prevent the Adulteration of Food, Drink, and Drugs. It lists the following contaminants found in wines; salt, copper sulphate, salts of lead or zinc, tobacco, opium, and Indian hemp. The US Food and Drug Act of 1906 went further, insisting on adequate labeling, especially for medicines. Why, oh why, do people contaminate stuff, and mislabel stuff, and just plain lie about stuff they produce for sale? We don’t have a useful answer, so we make regulations—not a great solution, but a necessary one.

Regulations reflect imperfect motives. Regulations on food and medicine are meant to prevent poisonings, but they can be poisonous in themselves. Too often they are preceded by entrenched ideologies that colour how regulators view facts: which ones they notice, and which ones they ignore. Many prohibitionist governments these days claim to follow evidence-based policies; they just hallucinate the inconvenient evidence out of existence. Regulators can be so biased that they are unable to respond to alternative views with any measure of reason. Some regulations, like those founded on racism, are toxic from the outset. Others, like the limits currently placed on how much cannabis you can store, are simply overdone.

Given our flawed condition, we should say that those regulations are best that are the least restrictive of all the available, effective alternatives.

2. WHAT ARE REGULATIONS IN A DEMOCRACY?

Democratic societies need regulations on which people can agree, and which they will follow voluntarily. For this purpose, regulations must make sense, especially to their target group. If they don’t make sense, no one will care to comply. If no one complies, the society must resort to force: arrest, prosecution, imprisonment, forfeiture, and physical violence. Resorting to force undermines democracy.

Societies that value equality before the law need, in addition, regulations that are easily enforceable. Regulations that are hard to enforce, or expensive to enforce, will be imposed selectively. Some people will get nailed; some won’t. That kind of inequality has been a defining characteristic of cannabis prohibition, for patients, elective users, and activists.

The overarching goal for all regulations in liberal democracies should be the care and feeding of liberal democracy.

3. WHAT IS AUTHORITY?

There are several types of authority: inherited authority, as in monarchies; dictatorial authority based on superior police or military power; charismatic authority, the province of magnetic personalities; and legal authority in democracies. Then there is authority as exercised by the surgeon in the operating theatre, the master gardener at the Royal Botanical Gardens, and the head chef in the Michelin Starred kitchen. That authority rests on superior experience and knowledge. Knowledge-based authority is central to the legalize cannabis movement.

There are several types of authority: inherited authority, as in monarchies; dictatorial authority based on superior police or military power; charismatic authority, the province of magnetic personalities; and legal authority in democracies. Then there is authority as exercised by the surgeon in the operating theatre, the master gardener at the Royal Botanical Gardens, and the head chef in the Michelin Starred kitchen. That authority rests on superior experience and knowledge. Knowledge-based authority is central to the legalize cannabis movement.

In recent times some regulators have recognized the expert authority of cannabis patients and activists. When it legalized cannabis in 2013, the State of Colorado recognized the expertise of medical cannabis dispensary owners. Regulators left them in place, and invited them to apply for additional, recreational cannabis licenses, thus letting them lead the way. When the City of Victoria, BC decided last May to regulate medical cannabis dispensaries in the city, it granted regulatory authority to the Canadian Association of Medical Cannabis Dispensaries (CAMCD); CAMCD already had a set of well-crafted regulations. Unhappily, this kind of recognition is rare.

Regulators that target a culture must recognize its particular expertise, and grant it authority to craft regulations suitable to its needs.

4. ABOUT KARMA

The best regulations aid the accumulation of good karma. By this I mean that they narrow the gap between poverty and wealth in the cannabis community by meeting the needs of low-income participants. Regulations can do this in two main ways: they can allow home growing, and they can allow citizens to give gifts of cannabis, or to share quantities of cannabis, with others. They can also provide incentives to non-profit dispensaries and shops.

5. EXISTING REGULATIONS

With these ideas in mind, let’s look at recent regulatory examples: US States: Colorado, Washington, Oregon, and Alaska; and the Canadian city of Vancouver BC in regulating medical cannabis dispensaries. We can rate them on the points noted earlier: moderation in restrictiveness; recognition of expertise, understandability to consumers, and karma.

With these ideas in mind, let’s look at recent regulatory examples: US States: Colorado, Washington, Oregon, and Alaska; and the Canadian city of Vancouver BC in regulating medical cannabis dispensaries. We can rate them on the points noted earlier: moderation in restrictiveness; recognition of expertise, understandability to consumers, and karma.

On every point, Washington State’s regulations rate poorly. They can make little sense to patients, currently in the process of being stuffed—if all appeals fail—into a recreational model designed by a Liquor Control Board, insensitive to medical needs. They demonstrate no respect for patient expertise. They score appallingly on the karmic scale. Washington’s regulations allow no home growing, no gifting or sharing of cannabis, and little respite from a burdensome tax scheme. Washington’s patients need all possible encouragements.

Colorado, Alaska and Oregon maintain systems of medical dispensaries, and respect the knowledge base of patients and cannabis friendly medical professionals. They score high on karma: they allow home gardens. Colorado allows 6 plants per adult, and a maximum of 12 per household. Oregon has a more patient sensitive system: designated growers can have gardens for up to 4 patients each: 6 mature plants and 18 seedlings per patient. Recreational users can grow 4 plants per household. Alaska allows up to 6 plants per household only, 3 to be mature at any one time. All three states allow gifts of up to an ounce at a time. Overall, their regulations are understandable, and thus palatable.

Where it comes to rules for consumption, however, all four score poorly on sense and acceptability. No state allows cannabis in public spaces that have traditionally welcomed alcohol. In no state can citizens smoke, vape, or eat cannabis at concerts, sports events, public parks, bars or social clubs. No state allows vape lounges. These regulations cannot make sense to cannabis fans. Indeed, they make little sense at all, except as reefer madness hangovers. The states score equally poorly on their rules for possession. Citizens can carry up to an ounce; rules vary on how much of this or that adults may have in their homes. As all states allow unlimited amounts of liquor per household, these regulations are equally senseless. Besides, they are not easily enforced. On both these grounds it must be said that whilst cannabis is legal in some places, cannabis culture is not yet legal anywhere.

Where it comes to rules for consumption, however, all four score poorly on sense and acceptability. No state allows cannabis in public spaces that have traditionally welcomed alcohol. In no state can citizens smoke, vape, or eat cannabis at concerts, sports events, public parks, bars or social clubs. No state allows vape lounges. These regulations cannot make sense to cannabis fans. Indeed, they make little sense at all, except as reefer madness hangovers. The states score equally poorly on their rules for possession. Citizens can carry up to an ounce; rules vary on how much of this or that adults may have in their homes. As all states allow unlimited amounts of liquor per household, these regulations are equally senseless. Besides, they are not easily enforced. On both these grounds it must be said that whilst cannabis is legal in some places, cannabis culture is not yet legal anywhere.

Vancouver BC is a special case, as the City Council’s regulations pertain only to medical cannabis dispensaries. Thus far the city has elected to ban the sale of cookies, cakes and confections, as councillors fear that such things will appeal to children. This regulation is overdone, but understandable. More problematic is the Council’s plan to de-cluster dispensaries by insisting that they be at least 300 metres apart. If these rules are followed, Vancouver’s older, experienced dispensaries may have to shut down. Ditto for many others. This regulation rates poorly on understandability. All businesses cluster. Cities have restaurant districts, financial districts, and antique shop districts. Shopping malls are little more than strings of clothing stores. Nevertheless, Vancouver rates high on recognizing expertise, as noted earlier. It also ranks high on karma: it provides drastically reduced licensing fees for nonprofit dispensaries.

I end this blog by remembering that these cannabis regulations were designed in defiance of federal authorities, and function uneasily under the federal eye. We must give their proponents high marks for bravery. That being said, my crystal ball reveals dizzying opportunities for civil disobedience, citizens’ initiatives, and strategic voting. Let’s keep helping each other. It’s slow, but it works.