Phantasmagoria:

1a. Images seen with the magic lantern, 19th century precursor to moving pictures

2a. A constantly shifting, complex succession of things seen or imagined as in a dream or fever state…

Spinners of future tales on cannabis history—fictional or non—will need to draw on the succession of dreams and fever states that have created and maintained prohibition. Here are some to consider.

1. RACIALLY BASED HATRED

Intolerance for the cannabis plant in White North America is founded on its imagined special attractiveness to non-white locals or visible immigrants. In the 1930s black innovative jazz musicians were known to like cannabis; Proto-Drug Czar Harry Anslinger declared the music and its fans degenerate. Early Mexican immigrants were seen to smoke it; newspapers and local authorities called them crazy and dangerous. Canada’s early prohibitionist, Emily Murphy, published regurgitated versions of American police cannabis reports, and wrote menacingly of black persons living in Nova Scotia. Racially biased laws ban the plant and punish consumers—especially the ones lawmakers never liked in the first place.

2. WHITE SUPREMACISM

North America has a long history of white supremacist feeling, complete with clubs, clans and associations. From the outset North American laws targeted and nullified First Nations Peoples, African Americans, Asians and other visible immigrants. Then in the 1960s something new happened. Many white young people began to embrace cannabis, not the usual white thing to do. Predictably they tried but were unable to create a positive change in laws on cannabis. They failed to endear themselves to authorities and much of the public. They identified with non-whites. They worked for civil rights, and voters’ rights. They refused to be drafted into wars of aggression, and burned their draft cards. They adopted native and southern styles of dress, and embraced native spirituality. They studied Zen Cookery. They supported gay people—not considered properly white. They supported economic equality—too friendly to non-whites.

3. POST-COLONIAL PARANOIA

Popular news reports in North America in the 1940s and 50s carried the message that people of colour used ‘drugs’ deliberately to infect whites, especially their women and youth. They did this, so the story went, as part of a strategy to weaken them, conquer them and gain political control of the continent. These reports were little other than bad post-colonial conscience masquerading as reason. Where there is paranoia, there will be calls for purging. Think witch burning. Anti-cannabis laws are meant to induce North America to vomit up its infectious elements, plants and all, isolate them and keep them isolated.

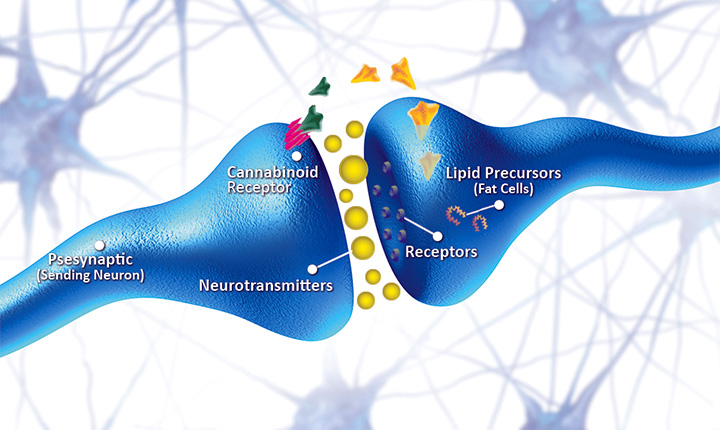

4. BOTANICAL DEMONISM

Reefer madness ideology as expressed in film and in the popular press, created a new dramatic character: Cannabis the Unholy, a plant. CU harbours a demon that sucks the sanity from the minds that it attracts. This notion was never written into law, but North American lawmakers and enforcers continue to behave as if had been. The anti-cannabis lobby persists in the view that if legalized, cannabis will possess the minds of teens and the unborn, rendering them, if not unholy, at least dull and lazy.

5. NEO LIBERALISM/NEOCONSERVATISM

Some writers call contemporary right wing thought neo-conservative because it is so anti-liberal. Others call it neo-liberal because it trashes the traditional, conservative concept of honour, seeing it as a sign of weakness, and a barrier to business.

Until the late 1970s, liberal ideals informed most North American public policy. It was generally believed that citizens of a just nation should be granted all liberties consistent with liberty for all. They were to be restrained, in other words, only if they threatened the freedom of others. This formula for liberalism dates from the 19th century iconic writings of John Stuart Mill. But it is given extraordinary, sustained, and pragmatic expression, in Peter McWilliams’ work of the year 2000, Ain’t Nobody’s Business If You Do. That was the year McWilliams, well-remembered victim of the war on cannabis, died.

Ain’t Nobody’s Business was published fifteen years after ruling governments in North America had begun to abandon liberalism for harsher, more competitive principles. In the galaxies of Ronald Reagan and Brian Mulroney (as with the infamous Margaret Thatcher) ‘liberal’ meant cowardly. It meant setting out welcome mats for illegal immigrants, criminals, vagrants, consumers of street drugs, unruly youth and welfare bums. At the cost, one should add, of starving the military, which for neo-cons, has always to be kept well fed.

6. HIGH ALERT MILITARISM.

This is the mindset of Harper’s Canada, and post 9/11 America. It is destructively anti-democratic. Cannabis connoisseurs do not fit comfortably in this world. They resent government surveillance and military aggression. They support environmental issues. They see the anti-terror mentality as a strategy for retaining power. America has a long democratic tradition of states’ rights and ballot initiatives, and activists on that side of the border have become brilliant at using them. Having a Democratic president hasn’t harmed them either. Canadians lack this tradition; connoisseurs here will need to elect some quality, enlightened leaders. Or they’ll need to become them.

This is the mindset of Harper’s Canada, and post 9/11 America. It is destructively anti-democratic. Cannabis connoisseurs do not fit comfortably in this world. They resent government surveillance and military aggression. They support environmental issues. They see the anti-terror mentality as a strategy for retaining power. America has a long democratic tradition of states’ rights and ballot initiatives, and activists on that side of the border have become brilliant at using them. Having a Democratic president hasn’t harmed them either. Canadians lack this tradition; connoisseurs here will need to elect some quality, enlightened leaders. Or they’ll need to become them.

7. POLICE-BOUND JOURNALISM

Media bias theory tells us that where there are more independent reporters, there will be a wider range of views for citizens to access. The theory seems obvious. But it does nothing to explain mainstream media reporting on cannabis.

This century has seen stifling media amalgamation—in Canada, media squelching as well. Most of our mainstream news sources do little more than repeat what the DEA/RCMP tell them. With them money is the primary concern; drug police info is politically safe and cheap. In the mid 20th century the media were less amalgamated, so there were more independent news sources. Still, mainstream journalists simply repeated what law enforcement told them. In the 1920s and 30s North Americans had access to still more local newspapers and magazines, each expressing a distinctive viewpoint. But about cannabis, journalists wrote down, and publishers printed, whatever police and the bureaus of narcotics told them. This is an old marriage; it needs to end.

A few major newspapers, of course, have recently endorsed legalization, and new journalists are jumping aboard. But that’s largely a measure of how well cannabis activists have been doing at changing public opinion.

8. CREEPING ONE-DIMENSIONALISM

Elected leaders restrict themselves more and more to talking points, and speak to the media in shorter and shorter phrases. The current political sound bite is seven seconds long. The sad fact is, electoral politics has been taken over by beauticians, the professional controllers of photo ops and packagers of government messages. None of these developments does a bit of good for cannabis legalization or any other serious issue.

9. AGGESSIVE IRRATIONALISM

We’ve all seen media accounts that confuse cause with effect, and correlation with causation. Cannabis consumption among youth, we read, correlates with youth dropping out of school. But schools just fail to reach some youth. It should hardly surprise us if they seek out better experiences, and eventually leave. And maybe cannabis consumption among youth correlates with a preference for cotton socks, or at least a choice in music. Don’t they teach logic in journalism schools any more?

Here is my favorite. Prohibition lobbyists set the bar for legal cannabis far above the bar they set for all other pleasures. For alcohol, tobacco, caffeine, sugary foods, credit cards, gambling, video games, fast cars, the Internet, and everything else people like, there are widely tolerated addiction rates. For cannabis, well in the groove, there is none. This isn’t just nonsense. It’s phantasmagorical nonsense.

I HAVE CALLED THIS BLOG A GALLERY OF PHANTASMAGORIA

Exhibits 1 to 9 are not directly related; but they share an important quality: malevolent absurdity, a robust fever state. They also have synergy, if that’s not too slick sounding a term. Simplistic, shallow news reporting, for example, gives strength to extremism in politics. Faulty logic is helpful to leaders with hidden undemocratic agendas. Phantasmagorical thinking is blind and dangerous. Cannabis activism isn’t. That’s why it has managed so well to recruit doctors, scientists, scholars, lawyers and judges. In nations addicted to lunacy, activists become the guardians of reason.

Judith Stamps holds a doctorate in political theory from the University of Toronto, and taught in the Political Science Department at the University of Victoria from 1990-2000. She is the author of Unthinking Modernity: Innis, McLuhan and the Frankfurt School, numerous journal articles, essays and letters to the editor. Judith is a member of Sensible BC and was very active in the campaign to decriminalize, and ultimately legalize, marijuana in that province. Her current writing focuses on cannabis history and the history of prohibition. You can check in on her current work by visiting her blog: judithstamps.ca

Read more by Cannabis Digest Editor Judith Stamps