Plus Thoughts on Mark Haden’s Attempt To Make Cannabis Boring

A few days ago, On July 10, 2014, CBC News ran an article describing Mark Haden’s take on legalizing marijuana in BC.1 The province, says the UBC adjunct professor, should apply to the federal government for a ‘section 56’ exemption. Hmm. It’s tempting to remind the good professor, and the CBC, that this idea stood at the centre of Sensible BC’s draft bill, presented in 2013 as part its attempt to force a referendum on cannabis in BC. But one mustn’t quibble. Haden here makes four main points. First, public health is guided by evidence; BC, on an experimental ‘section 56’ basis, should be there to provide it. Second, if it does, its marijuana outlets should not to be located at ground level. Third, these outlets should look drab and boring. And fourth—here he offers a pre-conclusion–the experiment is sure to lead to decreased cannabis consumption. Whether by “decreased” Haden means fewer partakers, or just less pot for each, he doesn’t say.

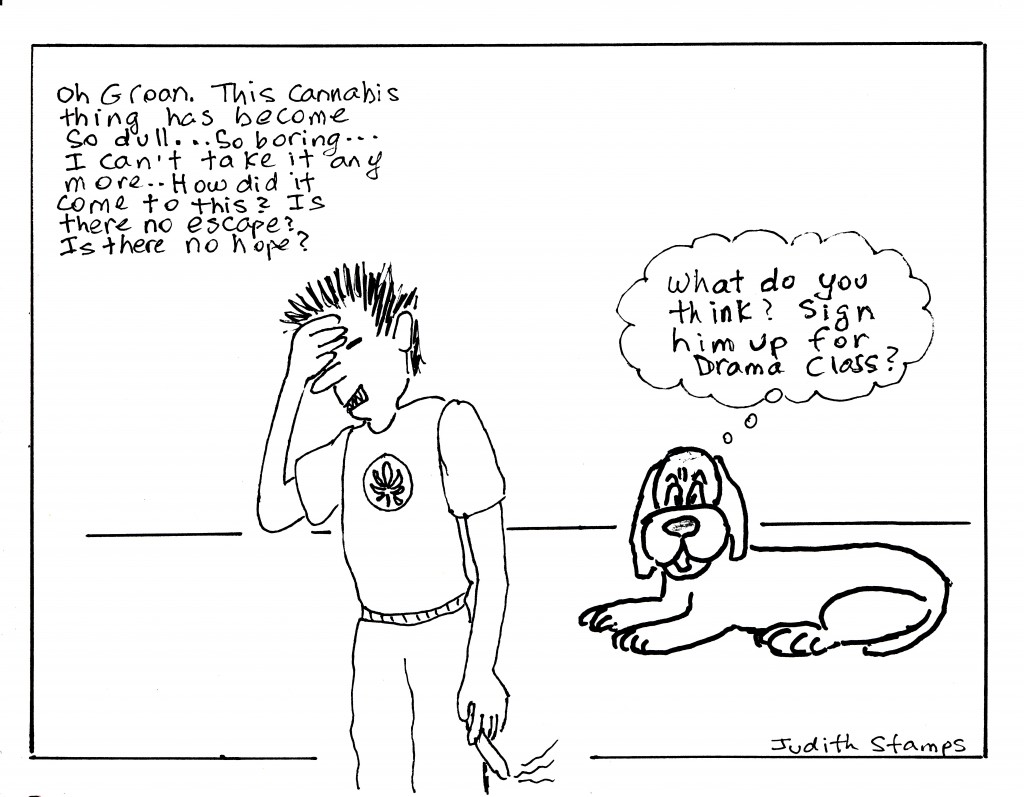

Public Health guided by evidence? Not around here it isn’t. Ask the medical marijuana community. A minor point, perhaps. But here’s the major one. Why the required inconvenience of stairs or elevators? Why the mandated drabness? Why the expectation, apparently desirable, that we will thus suppress, maybe even repress, demand? One has to wonder if Haden has experienced much good cannabis. Maybe he doesn’t understand or has never been told much about the plant’s beneficial effects. Or maybe he’s forgotten. If he has, it is possible that we are partially to blame, we, that is, who love the plant. The fact is, we rarely rhapsodize about its effects. Not in detail, anyway. We’re so busy defending individual rights, cursing law enforcement, and battling media sponsored lies. We spend our time, cross-eyed, and reeling from contorted discussions about schizophrenia, or the teen-age brain, or crime rates, or prospective pricing. So for Haden, and for the rest of us, I offer two of my favourite tributes to marijuana; the first from the late 1920s, and the second, contemporary. Here’s to the utter meaninglessness of drab environments.

I introduce first, Jewish German essayist, literary critic, and cultural analyst, Walter Benjamin (1892-1940). Over a number of years, and under the supervision of a doctor friend, Benjamin engaged in a series of hashish experiences, each of which he documented.2 This one, conducted in Marseilles, begins around suppertime on September 28, 1928.3 Sitting on his bed, Benjamin consumes a dose of hashish paste, and leaves his small hotel room to meander the city streets. He visits cafes, restaurants, and bars featuring jazz. He observes the scenes of the street, the texture of its paving stones and the finer texture of his inner life. He provides, in his memoir, the following observations.

Hashish summons the “ecstasy of the trance,” an experience whose effect is to heighten the memorability of thoughts and events that take place under its spell. Its method is to cut itself (and us) off from every day reality, the cut leaving fine, prismatic edges that form figures easily remembered, something like flowers. More succinctly, it throws events and objects alike into high relief, preserving them, flower-like for one’s journal.

Benjamin considers next, his métier. He is a writer of prose. The writer understands the trance best, he offers, through the image of Ariadne’s thread. Ariadne of Greek mythology is keeper of the Cretan Labyrinth, the maze at the centre of which dwells the dreaded Minotaur: half man, half beast. According to legend, Ariadne’s lover, Theseus, sets out to slay the brute. To ensure that he will find his way out again, she unwinds a skein of thread and lays it along the labyrinth’s pathway for him to follow. For Benjamin, the skein symbolizes the essence of creation; the act of unwinding, the dynamic image of the artist’s journey, its cave-like twists and turns, its anticipation of dangers lurking. The skein, artfully wound (as skeins are known to be) is the gnarled root, the chiseled face, the darkened courtyard, whose mysteries are to be unraveled. Unraveling stands thus at the core of the writer’s enterprise. “Under hashish,” he writes, “we are enraptured prose-beings in the highest power.”

Not so enraptured, however, as to refuse a “final ice cream.” He’s already had steamed oysters, pate de Lyon, and Cassis wine poured over ice cubes. Now past the peak of his journey, he calls to mind its first signpost, the one announcing that the plant had begun its work: a feeling of amorous joy dispensed by watching some fringes blown about by the wind. “When I recall this state,” he writes, “I should like to believe that hashish persuades nature to permit us—for less egotistic purposes—that squandering of existence that we know in love.” ‘For less egotistic purposes’ means something like this. Ordinary love, as provided by nature, can be bounded by expectations that it produce children, or social cohesion, or economic stability. It can be constrained culturally and entrapped in civil law. It can be harnessed. Hashish persuades nature to allow us a love unbound and unharnessed: the love of fringes blown by the wind, of mysteries unraveled, of their memories shaped and preserved by fine prismatic cutters.

Not so enraptured, however, as to refuse a “final ice cream.” He’s already had steamed oysters, pate de Lyon, and Cassis wine poured over ice cubes. Now past the peak of his journey, he calls to mind its first signpost, the one announcing that the plant had begun its work: a feeling of amorous joy dispensed by watching some fringes blown about by the wind. “When I recall this state,” he writes, “I should like to believe that hashish persuades nature to permit us—for less egotistic purposes—that squandering of existence that we know in love.” ‘For less egotistic purposes’ means something like this. Ordinary love, as provided by nature, can be bounded by expectations that it produce children, or social cohesion, or economic stability. It can be constrained culturally and entrapped in civil law. It can be harnessed. Hashish persuades nature to allow us a love unbound and unharnessed: the love of fringes blown by the wind, of mysteries unraveled, of their memories shaped and preserved by fine prismatic cutters.

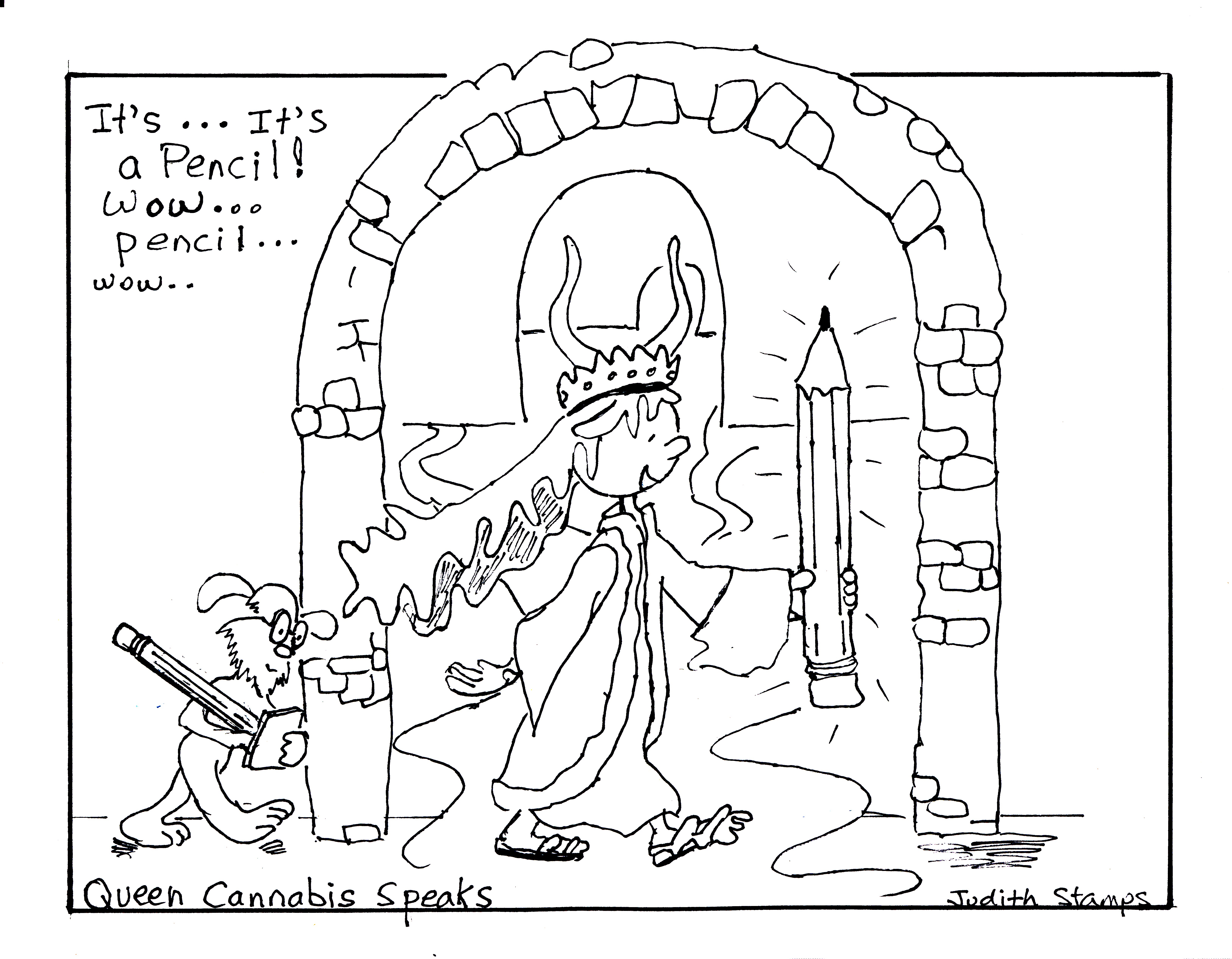

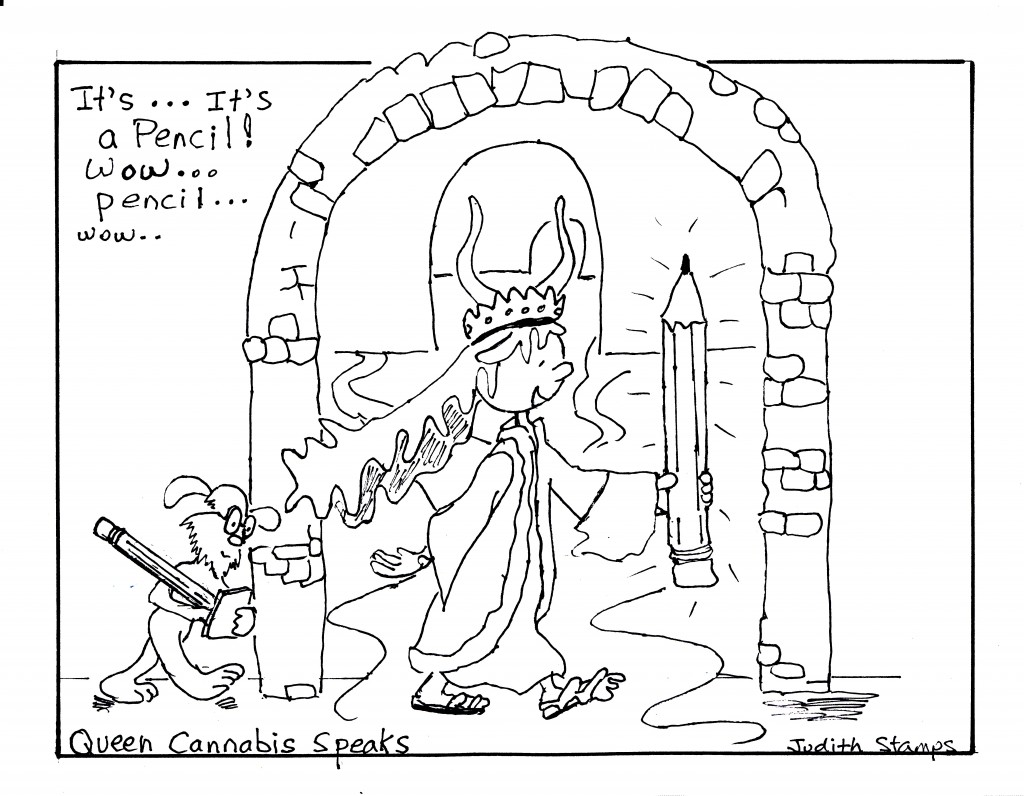

Many who have taken cannabis have noted its ability to heighten senses, to create an extraordinary engagement with sights, sounds and textures. Opinion is mixed, however, on how to comprehend these effects. They can create a kind of stunned, seemingly opaque form of present mindedness. This is a state frequently satirized through comic routines, buffoonery and slapstick humour. Let the following stoned dialogue stand as an example. Taken from Richard Chlorfene and Jack Margolis’ book, A Child’s Garden of Grass, it goes like this.

[su_quote]Virginia: What were we talking about?

Andy: You asked if I were hungry.

Virginia: Did I?

Andy: Yes.

Virginia: Well, are you?

Andy: Am I what?[/su_quote]

A contemporary, analytic view of this matter is provided by Michael Pollan’s work, The Botany of Desire: A Plant’s Eye View of the World. It is easy, but banal, he notes, to lampoon a mind-state in which you forget where you were in a mundane chain of thought. It is far more difficult adequately to put the force of this mind-state into words.

What Cannabis offers, in Pollan’s view, is a temporary lifting of the culturally conditioned, conceptual filters that we acquire over a lifetime. It offers to suspend prejudice. We distance ourselves from things, he argues, by calling them banal, by treating them ironically, or by reducing them to abstractions. Consider, for example, an ordinary pencil—my example, not Pollan’s. Stoned, we do not regard it as banal. For that we would have to keep in mind having dismissed pencils, at some point, as uninteresting. We do not view it ironically. For that we would have to recall some engagement with it. We are unlikely to theorize about it. For that we would have to place it in a category, acquired at some point in the past. Without this distance, we are left with its thing-ness: the slender, prismatic shape, the smooth, coloured surface, the smell of wood shavings, calling up a rainy day in grade one. For adults, Pollan argues: “Memory is the enemy of wonder.” Lifting it temporarily allows us to see again unsparingly, without motive or end goal. This is, in essence, why we toke.

But what should we think about all this forgetting? Critics disparage it, comics joke about it, and even sympathizers fear it. Is it bad? One has to realize, Pollan notes, that forgetting is neither an absence nor a malfunction. It is a positive act, essential to every healthy mind. We would hardly enjoy having to remember every face, every sentence, and every stimulus we have ever encountered. We would go mad. To survive, we need filters. Taken periodically, marijuana reconfigures these, at least for a time. Tokers are time travellers. Just sometimes, they are a bit stunned.

This brings us back to Haden. What would it take to set up drab environments for pot sales in BC? I say that it would require first, that we create teams of shopkeepers who are Deltas. A Delta is a member of a social class, described in Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, conditioned from babyhood to shun everything fine and beautiful. They would be happy with ‘dull,’ and would never take Cannabis. Of course we would know if they did. They would start sneaking in the Rasta posters and the sublimely blown glass pipes. They might start keeping journals, like Benjamin’s. Then there is the issue of having to avoid the street level. Aside from some mild inconvenience, this feature is likely to matter to no one at all. Would you shrink from a staircase? You might need an elevator.

So that leaves us with Haden’s prediction that, given these shops, there will be less partaking altogether. Less partaking of what, though? Less wonder? Less rapture? Less enjoyment? Truly, the neo-conservatives are right to despise this plant. Where would we be without all that banality, irony and abstraction?

[su_note note_color=”#cbffb5″]

2. For memoirs of cannabis use, it is common to cite a group of literary personae of mid nineteenth century France, who formed a hashish group, Le Club Des Hashischins. They wrote elaborate descriptions that are fun to read. But it is unclear from the historical record what exactly the members were taking. Poet Charles Baudelaire described their medicine as hashish mixed a small amount of opium. Others, notably fond of absinthe, were likely to have mixed in some of that too. Their accounts are so otherworldly, it seems unlikely that they are true portraits of cannabis.

3. “Hashisch in Marseilles” in Walter Benjamin, Reflections: Essays, Aphorisms, Biographical Writings, NY, Schocken Books, 1986

[/su_note]