A Drug Called Weed: A Restless Ramble on a Problem Concept

It is common to see posts that claim: cannabis is not a drug. This is an interesting claim, as it is both true and not true. More than that, I believe, it is a claim that, if explored, takes us to the heart of the controversy over this fiercely loved, and much maligned plant. Let us begin with language.

1.

The word ‘drug’ word stems from the 15th century Dutch term, droge, or droog, and a related Old French term, drogue, meaning ‘dry’. All three were used to indicate dried herbs, both culinary and medicinal; the words ‘drug’ and ‘dry’ thus have a common ancestor. Had these meanings remained stable, ‘drug’ would be the perfect category for cannabis. But they didn’t; the meaning of ‘drug’ has, to say the least, morphed.

2.

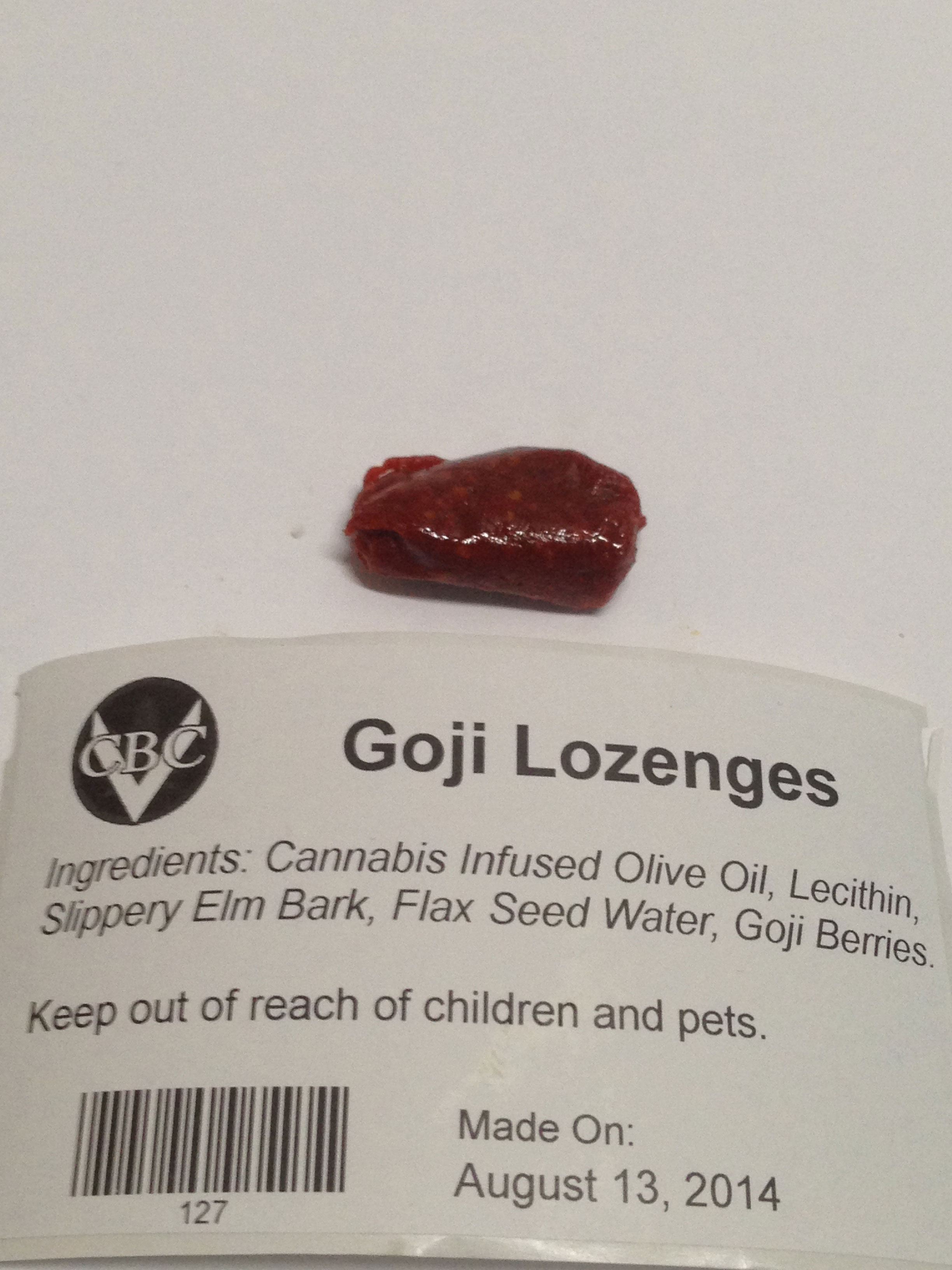

Fast-forward five hundred years, and ‘drug’ is a formal part of the English language, with a dictionary definition, rendered at its simplest: “A substance used as, or in, medicine.” My handy synonym finder lists it alongside medicine, remedy, narcotic, soporific, stimulant, and psychedelic. As cannabis can be all of the above, we would have no trouble listing it as a drug—if, that is, we lived by, and talked in, dictionary meanings.

Fast-forward five hundred years, and ‘drug’ is a formal part of the English language, with a dictionary definition, rendered at its simplest: “A substance used as, or in, medicine.” My handy synonym finder lists it alongside medicine, remedy, narcotic, soporific, stimulant, and psychedelic. As cannabis can be all of the above, we would have no trouble listing it as a drug—if, that is, we lived by, and talked in, dictionary meanings.

A commonly heard argument is that, since our socially acceptable drugs are mainly pharmaceuticals, and since pharmaceuticals are synthetic compounds, ‘drugs’ in this society are essentially synthetics. And in that case, cannabis should not be listed as a drug. This view, though it sounds sensible, is problematic. It is not uncommon for an English term to cover both natural and synthetic versions of its referent. Consider music, for example: acoustic and synthesized sounds, artfully arranged, are both called music. The same is true of intelligence: natural and artificial thinking, for better or worse, are both called intelligence. The words ‘textile’ and ‘food’ are used similarly. Seen alongside such examples, cannabis is undoubtedly a drug, albeit a natural one. The key difference, truly, is this: we’ve never had a war on music, or on intelligence, or on textiles, or on food.

Something happens to words that refer to taboos, or hated objects. They fragment. The people that employ them, and the media that represent them, sort the fragments mentally into separate, sealed compartments. This process, largely subliminal, can yield three or more irreconcilable versions of a word, with hardly anyone conscious of the fact. Here are some fragments of our word, ‘drug’.

Fragment One.

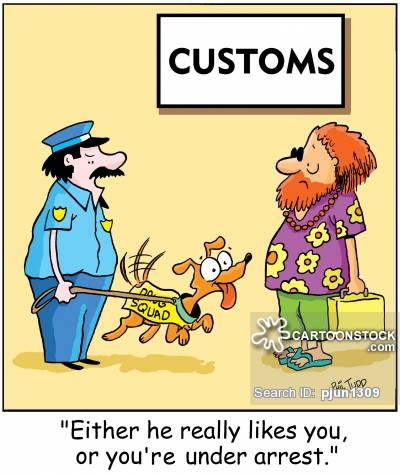

The best known of these occurs in the phrase, War on Drugs. This version excludes prescription drugs, and also popular, legal drugs such as alcohol and caffeine. It also refers pointedly to cannabis. “Just say no to drugs,” “Don’t do drugs,” “Drug Free America,” and “addicted to drugs,” all make use of this fragment. So do the phrases ‘drug dealer’, ‘drug bust’, and ‘drug rehab’. They all denote something that enslaves people. Media presentations on ‘drugs’ understood in this way, focus in the shallowest manner on arrests, seizures, and street prices.

Fragment Two.

A new mental compartment opens up when we walk through the doors of a drugstore: The Drug Mart, London Drugs, The Drug Emporium, Payless Drugs, Rexall Drugs, or Shoppers’ Drug Mart. They conjure memories. We can recollect, as children, navigating their toy sections, riffling through the children’s magazines, and drooling over the candy racks, and party stuff. We visit them now to buy cough syrup, Band-Aids, hot water bottles, magazines, stationery, holiday decorations, cat food, and cameras. And while we go to drugstores to buy drugs too, their glitzy settings hardly invite thinking about the fact. In truth, they hardly invite thinking at all.

A new mental compartment opens up when we walk through the doors of a drugstore: The Drug Mart, London Drugs, The Drug Emporium, Payless Drugs, Rexall Drugs, or Shoppers’ Drug Mart. They conjure memories. We can recollect, as children, navigating their toy sections, riffling through the children’s magazines, and drooling over the candy racks, and party stuff. We visit them now to buy cough syrup, Band-Aids, hot water bottles, magazines, stationery, holiday decorations, cat food, and cameras. And while we go to drugstores to buy drugs too, their glitzy settings hardly invite thinking about the fact. In truth, they hardly invite thinking at all.

Fragment Three. Then there are the drugs that are legal to use recreationally, but rarely go by the name, ‘drug’. These are tobacco, alcohol, caffeine, chocolate, and sugar. Our minds tuck them away, far from the concept, ‘drug’. How this mental manoeuvre is managed, I have no idea. But it constitutes a fragment in itself—the weirdest of the three. In Western culture these substances have gotten a free ride by remaining classified as something other than drugs. A liquor store is a drug store, as is a tobacconist’s. We’ve just learned to hallucinate them as something else.

It is no wonder, then, that cannabis activists resist the label, ‘drug’. But what do we do with such negative labels? It is sometimes possible for communities to shift the meanings of labels by re-appropriating them. The gay community, for example, has adopted the term ‘queer’; and the lesbian community has done the same with ‘dyke’. Black communities have re-appropriated the word, nigga’. But these, alas, were specialized terms. The word ‘drug’ is too broadly used, and is not a good candidate for re-appropriation.

It May, However, Be a Good Candidate for Radical Re-Thinking.

Especially interesting about drugs in Drug Fragments Two and Three is that they are never acknowledged to have psychoactive, or mood-altering effects. Society permits us, indeed, invites us, to drink wine, and love wine. But it does not permit us to feel intoxicated by it, not really. If we ever do get drunk, we apologize, or make a joke. Scan the pages of the wine magazines, and you will see elaborate descriptions of texture and flavour, a subject that has now reached the level of art. But nary a word will you see on psychoactive effects. The Western world invites us to delight in smoothness, and fruitiness, but never to feel warm, or fuzzy, or dizzy. The same is true for prescription drugs, like opioids. The literature on side effects will list sleepiness; it never tells you that you will get stoned. It has to be said, thus, that expressions of enjoyment, if drug facilitated, are just plain not acceptable.

Especially interesting about drugs in Drug Fragments Two and Three is that they are never acknowledged to have psychoactive, or mood-altering effects. Society permits us, indeed, invites us, to drink wine, and love wine. But it does not permit us to feel intoxicated by it, not really. If we ever do get drunk, we apologize, or make a joke. Scan the pages of the wine magazines, and you will see elaborate descriptions of texture and flavour, a subject that has now reached the level of art. But nary a word will you see on psychoactive effects. The Western world invites us to delight in smoothness, and fruitiness, but never to feel warm, or fuzzy, or dizzy. The same is true for prescription drugs, like opioids. The literature on side effects will list sleepiness; it never tells you that you will get stoned. It has to be said, thus, that expressions of enjoyment, if drug facilitated, are just plain not acceptable.

A psychoactive effect, for too many, is assumed mainly to cause reduced responsibility, or the breaching of established social barriers, or the breaking of taboos. Or it is regarded as a state of slavery. Or we believe that such an effect will turn us into degenerate, less intelligent, and less competent versions of ourselves. drug addictive. So, we just never mention these effects.

No such denial, however, is possible for illegal drugs. Everyone knows that cannabis will make you stoned, or lit, or baked, or something equally desirable. And now, oh horror, the Canadian Government is making it legal to get that way. There is no way that the Trudeau Liberals could have said: we are legalizing cannabis because Canadians might enjoy it. Nope. Post legalization, police will be out hunting down stoned people because, in Canada, being stoned in any fashion has never been acceptable. Not ever. The war on drugs has always been a war on psychoactive effects.

Science Doesn’t Help

It would be nice if more scientists and doctors would shed some light on this subject. They could, for example, help us by distinguishing dangerous psychoses from benign, temporary drug-induced states; or dementia from benign, pleasant states of fuzziness; or being crazy from just being high for a while. These are not the same. But on this matter, professionals don’t seem much more informed than the typical fear monger. Some of them, like members of the Canadian Medical Association, and employees at Health Canada, are the typical fear mongers.

So Is There a Solution?

Yes. Time, and forgetting. If, over the years, legal cannabis consumption turns into something like wine, or coffee consumption, cannabis will cease to be considered a drug, even when it is sold by Shopper’s Drug Mart. It will called bud, or weed, or some word not yet invented. The new, hyper-glossy bud magazines will feature articles on smoothness, and flavor, and relaxation, but not on the experience of being high. Within decades, there will be a new, cannabis commentary art form. And within centuries, ‘being high on cannabis’ will be something found on old maps, whose worlds no longer exist, but whose knowledge is guarded by secret societies such as the Knights of Cannabis, and The Order of Bud. At that point, I believe, cannabis fans will be left in peace. Of course it is also possible that, as a society, we will just get more real. But as I watch the new Canadian laws take shape, I’m not betting on it.