In 2001, in response to a court challenge, Medical Marijuana Access Regulations (MMAR) was implemented in Canada, allowing patients to grow their own medicine. This law gave them a level of peace. But the federal government remained hostile to the idea, and so were a number of BC municipalities. In 2012, the peace ended. Health Minister, Leona Aglukkaq, sounded an early alarm. The MMAR, she announced, was out of control. Designed initially for 500 patients, it had ballooned to a program for 30,000. There were gazillions of home growers, creating chaos. Some couldn’t wire grow lights properly and were causing house fires. Others were becoming associated with gangs. In any case, their plants were magnets for thieves, bringing violence to good neighbourhoods.

Predictably, in July 2013, Health Canada announced the repeal of the MMAR, and its replacement by a new program, the MMPR. There was to be no home cultivation, and patients were to place themselves in the hands of Licensed Producers (LPs.) Panic ensued. Within months, a 6,000 member Coalition Against Repeal had formed and seasoned lawyer, John Conroy, employed to challenge the law. Over Christmas prior to the hearing, John Conroy had seen an advertisement for Connie Carter and Susan Boyd’s book, Killer Weed: Marijuana Grow Ops, Media and Justice. As illustrated in Weedy Blues I, and II, this book analyses commonly skewed media accounts of indoor growing, and the subsequent distortions in public perception, especially as regards public safety. It counters the charges made by Aglukkaq in 2012. After the holidays, Conroy contacted Susan Boyd, and engaged her as an expert witness for his case. On March 14, 2014, a BC Federal Court judge heard the challenge, and granted an injunction, halting the MMPR in its progress. A constitutional hearing on the matter is set to take place in February 2015.

In a telephone interview, Boyd noted that Canada has systems of regulation. So why not just regulate growing? Good question. The best clue lies in the shifts in law enforcement priorities and government attitudes over the past two decades. Cited in Boyd’s affidavit is the fact that Canada’s overall crime rate is at an all time low. There was less crime in 2012 than in 1972. BC has seen the most dramatic decline: less crime in 2012 than in 1965. These figures are true not only for absolute numbers, but for severity of crime as well. Canada now sees less homicide, less assault, less theft, indeed, less violence in general than it did 40 years ago. There is less gang crime. In brief, there is no basis for panic. But there is a basis for confusion. According to Statistics Canada, drug related crime has risen steadily since the early 1990s. The year 2011 saw an increase of 4.3% over 2010; 2010 saw an increase of 10.2% over 2009, and so on. So here is the clue. In the 1990s, law enforcement agencies, in particular, the RCMP, began targeting drug users. Drug arrests rose, and so did the associated crime rate; pure magic. Moreover, 52% of all drug arrests in 2010, and 69% in 2011, were for cannabis possession.

It is little wonder, then, that medicinal growers were offered no benign system of regulation. They appeared to be part of a crime wave, a point that goes to the heart of the problem for marijuana fans today. By the 1990s, it must have been clear to anyone who was looking that there were fewer violent criminals for Canadian law enforcement officers to chase. Judging from the numbers listed above, they then switched gears, and focused on the nonviolent ones. For reasons the reader will have to supply, they exhibited a special appetite for pot smokers. They exhibited as well, the circularity in logic central to prohibitionist practices. It goes like this. You start arresting folks for smoking weed, and then announce a spike in the crime rate. You use the spiked figures to justify harsher penalties and extra money for law enforcement. You take the extra money, and arrest more folks. You then repeat.

These manoeuvres sound loony enough, but there is more. Exercises in slippery logic are illustrated further by the Harper government’s obsession with indoor growing, licensed or otherwise. In her affidavit, Boyd makes this clear and powerful point. Regardless of what one hears about “grow ops” from ‘tough on crime’ politicians and law enforcement agents, the numbers tell us that their central targets are neither growers nor sellers, but citizens who toke. The concern with “grow ops” is a political bait and switch. Or maybe it’s just plain lying. Either way as regards the MMPR, one has to conclude that problems associated with indoor growing have never really been the issue.

Neither is safety. According to an influential report by Len Garis, Surrey’s Fire Chief, homes with “grow ops” are 24 times more likely to catch fire than homes without them. Whatever this number means, it is a figure repeated often, both in safety pamphlets and in the press. Alas, neither insight nor analysis alters the fact that your neighbour may well have bought Garis’ line. So I thought I would spice up this blog with some number inquiry of my own. The following account is intended to provide some facts that you can present to folks who rave about “grow op” fires.

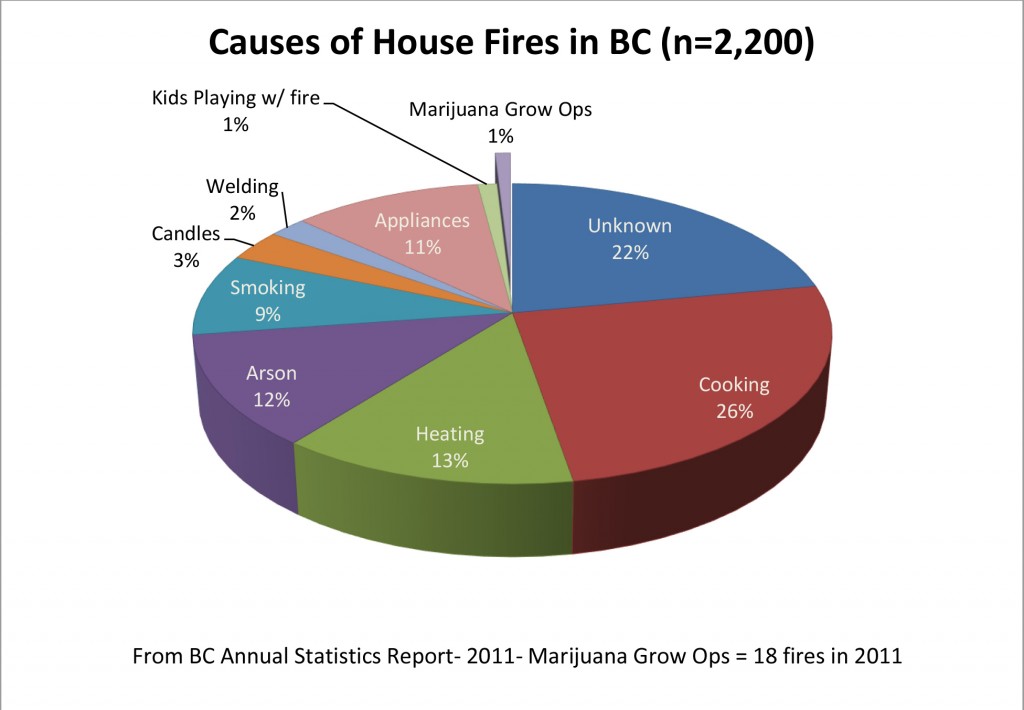

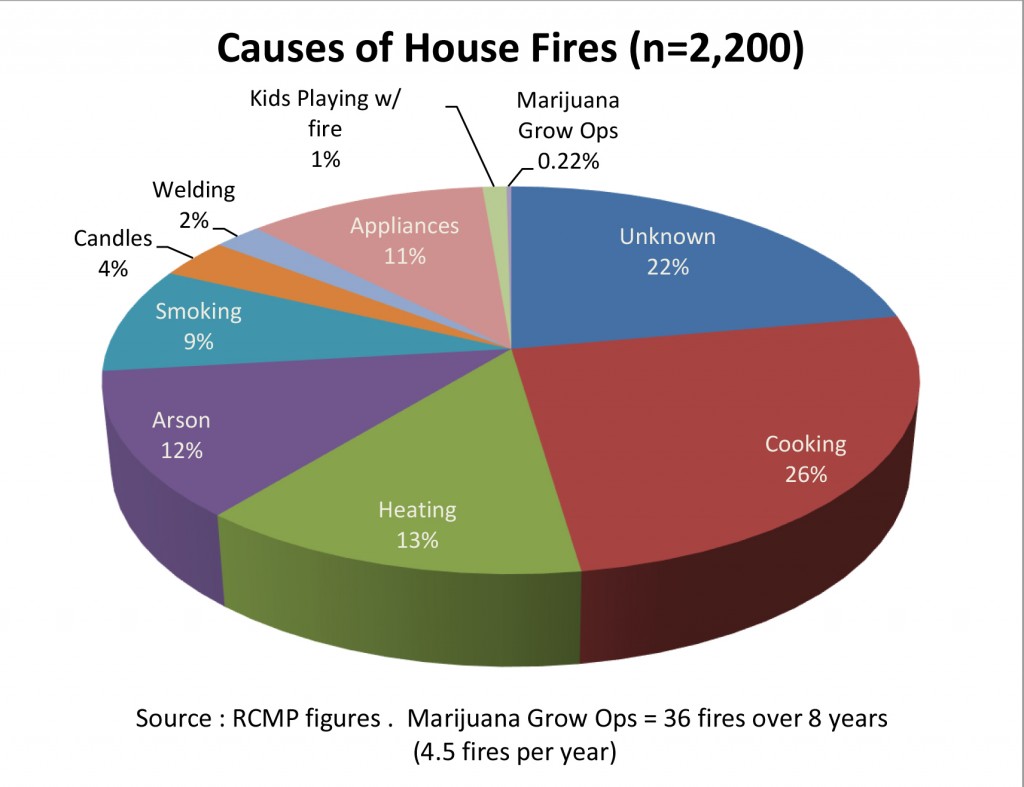

There are three online sources for fire safety figures: a 2007 study, Fire Losses in Canada, prepared for the Office of the Fire Commissioner, Alberta Municipal Affairs; a 2009 report by the Council of Canadian Fire Marshalls and Fire Commissioners; and the 2002-2011 BC Annual Statistical Fire Report. They tell us this. There are, on average, 2,200 residential fires in BC each year. Their causes, by percentage and in descending order are: 23% cooking; 20% unknown; 12% heating; 11% arson; 8% regular wiring; 8% smoking; 3% candles; 2% welding; 2% each for various appliances such as dryers and toasters, and 1% for kids playing with fire.

Only the BC Annual Statistical Fire Report mentions indoor marijuana cultivation, with figures given for 2011. Apparently, there were 18 indoor grow related fires in that year. An article in The Vancouver Sun on April 1, 2014 provides a different figure. It states that there were 36 such fires in the last 8 years. The Sun tells us in addition that 9 of those were at licensed grows. Thus, according to this source, there have been 4.5 fires per year from indoor growing, including just over one per year caused by medical growers. As demonstrated by the accompanying pie charts, there is a reason that this fire data is never expressed in percentages. They are absurdly low. So tell the folks to rest easy. Should the province burn, it will not be from cannabis.

It will not be from panic either, or so we hope. I began this blog by noting that Canadian medical marijuana patients acquired the right to grow their own plants in 2001. As described in Weedy Blues I, and II, some of BC’s municipalities were not pleased. In 2005, frustrated by Ottawa’s seemingly slack attitude, they launched a series of automatic and distressing safety inspections intended to eradicate home growing. By 2011, citizens had rebelled, and automatic inspections ceased. Since that time, Ottawa has taken the lead. In 2012, the Harper government produced its Safe Streets and Communities Act, notorious for its introduction of mandatory minimums, and its intention to build new prisons. In 2013, evidently not content, it aspired to end all home medicinal cultivation. Clearly, this has been the decade of The Battle to Reinstate Prohibition. Fought at both local and federal levels, its strongest weapon has been the ability to create panic over public safety. If the fire chiefs are to be believed, growing weed makes us 24 times more likely to burn our cities. Studies like that produced by Carter and Boyd, and blogs such as these, must strive to lay this nonsense finally and completely to rest.

Judith Stamps, June 15, 2014.