Battling Daren the Lion

This is the story of Educators For Sensible Drug Policy. It begins in 2001, when 21-year-old Adam Jones, an education major at the University of Montana at Billings, was arrested for possession of ½ gram of psilocybin mushrooms. He was sentenced to five years in prison, a sentence later lightened to two months served, plus three years probation. Upon release, he found that, as a “convicted felon,” he no longer qualified for a student grant or loan. The creature responsible for his plight was the Higher Education Act (HEA). HEA had been signed into law by Johnson in 1965, and reauthorized eight times thereafter. Jones became an activist. That year, he started the Billings Chapter of NORML, with the idea of lobbying for medical marijuana in his state. In short order, after travelling to Helena, Montana to testify in favour of a medical marijuana bill without informing his parole officer, he was rearrested and re-jailed.

In 2002, Jones attended a conference at Anaheim, California, hosted by Students for Sensible Drug Policy (SSDP) and the Marijuana Policy Project (MPP). The event was a smashing success. There were three hundred students, and veteran activists such as Ethan Russo, Senior Medical Adviser to the Cannabinoid Research Institute; Ethan Nadelmann of the Drug Policy Alliance (DPA); and former US Surgeon General, Jocelyn Elders. Set against the surreal backdrop of Anaheim’s Hilton—think multitudes of kiddies sporting Disney mouse ears–the conference inspired a new idea. Jones was an admirer of Law Enforcement Against Prohibition (LEAP), founded the previous March by five police officers. He decided that the world needed a similar organization, but for educators. He chose the name, Teachers Against Prohibition (TAP), and ran the idea by student representatives from the State University of New York, Richard Lake of DrugSense, and others. By early 2003 TAP, modeled after LEAP, had acquired thirty-five members, and was set to seek the endorsement of the National Teacher’s Association.

Then in 2003, Jones organized a benefit concert for the Billings SSDP and NORML, to be held on Friday, May 30 at the local Eagle Lodge. He hired bands, and advertised the event both on radio and the local press. It was not to be. On Thursday, May 29, he was rearrested. He had failed to report a change in workplace supervisors to his probation officer. He was ordered to provide a urine sample. When the test came back positive for drugs, he was jailed. Two days later, when a lab test showed the result to be a false positive, he was released. Meanwhile, plans for the benefit crumbled. Local DEA had seen the ads. They marched over to Eagle Lodge, waving a copy of America’s Drug Anti-Proliferation Act. Sponsored by Senator Joe Biden that same year, the Act made it illegal to provide a physical space for illicit drug use. DEA officers warned the owners that should one joint appear at this event, they would be fined $250,000.00. Sufficiently panicked, they backed out. So did Jones. Now reeling, he withdrew from activism.

Meanwhile in Canada, Judith Renaud was serving as principal at a small school on BC’s North Coast. She had been there since 2001, and had been witnessing incarcerations, despair, and suicide–effects of marijuana prohibition. She had already decided to dedicate her career to ending the war on this plant. She had joined an online activist group that revolved around American activist Richard Lake. Lake is editor of DrugSense’s Media Awareness Project (MAP), an impressive online archive of news and opinion pieces related to drug policy. They had met through a common listserv. She had also been in touch with Jones. When Jones’ world fell apart, he asked if she would be willing to take on TAP’s Canadian wing. Renaud conferred with Lake. She accepted the task but decided, with Lake, that the group needed new name. They wanted it to stand for rather than against something. Inspired perhaps by SSDP, they chose Educators For Sensible Drug Policy (EFSDP).

Meanwhile in Canada, Judith Renaud was serving as principal at a small school on BC’s North Coast. She had been there since 2001, and had been witnessing incarcerations, despair, and suicide–effects of marijuana prohibition. She had already decided to dedicate her career to ending the war on this plant. She had joined an online activist group that revolved around American activist Richard Lake. Lake is editor of DrugSense’s Media Awareness Project (MAP), an impressive online archive of news and opinion pieces related to drug policy. They had met through a common listserv. She had also been in touch with Jones. When Jones’ world fell apart, he asked if she would be willing to take on TAP’s Canadian wing. Renaud conferred with Lake. She accepted the task but decided, with Lake, that the group needed new name. They wanted it to stand for rather than against something. Inspired perhaps by SSDP, they chose Educators For Sensible Drug Policy (EFSDP).

EFSDP is a coalition of educators who share the view that prohibition is destructive and futile. The group maintains a speaker’s bureau, and encourages letter writing to editors, elected representatives and policy makers. Its members speak at conferences: Renaud, its executive director, attended NORML Canada’s first National Conference, hosted by CHAMPS EXPO earlier this year. She is a member of Stop the Violence BC, and of NORML Canada. Herb Couch, EFSDP’s director for Western Canada, and my interviewee for this blog, has been a “newshawk” for MAP–providing articles for its archive–since 1998. He joined the group in 2004. The organization has affiliates in New Zealand, Australia and Japan. Yet it remains, by Couch’s account, small, about 150 strong, and mostly online. It has more influence in Canada than elsewhere. EFSDP’s aim to “harness the weight and credibility of the teaching professions to bring about an enlightened drug policy.” In what follows, we examine a primary battleground for doing just that.

One of EFSDP’s daemons is the DEA/RCMP led Drug Abuse Resistance Education (DARE) program taught by RCMP officers in all Canadian provinces, except Quebec. DARE is US based, and was founded in 1983 under the Reagan administration. Its first mascot was Hanna Barbera’s Yogi Bear. Yogi, it seems, was a prohibitionist. DARE produces teaching materials for instructors and workbooks for children. Wikipedia calls them “a demand side drug control strategy of America’s War on Drugs.” DARE BC was established in 2003. It is a registered charity, supported by most Legions, six municipalities, Imperial Oil, Shell Canada, and Husky Energy. Officers wishing to teach the course in BC lobby school principals. The program is taught in over 120 communities, delivered by 250 RCMP officers, and has thus far reached over 100,000 children. In BC it is taught in Grades Five and Six.

One of EFSDP’s daemons is the DEA/RCMP led Drug Abuse Resistance Education (DARE) program taught by RCMP officers in all Canadian provinces, except Quebec. DARE is US based, and was founded in 1983 under the Reagan administration. Its first mascot was Hanna Barbera’s Yogi Bear. Yogi, it seems, was a prohibitionist. DARE produces teaching materials for instructors and workbooks for children. Wikipedia calls them “a demand side drug control strategy of America’s War on Drugs.” DARE BC was established in 2003. It is a registered charity, supported by most Legions, six municipalities, Imperial Oil, Shell Canada, and Husky Energy. Officers wishing to teach the course in BC lobby school principals. The program is taught in over 120 communities, delivered by 250 RCMP officers, and has thus far reached over 100,000 children. In BC it is taught in Grades Five and Six.

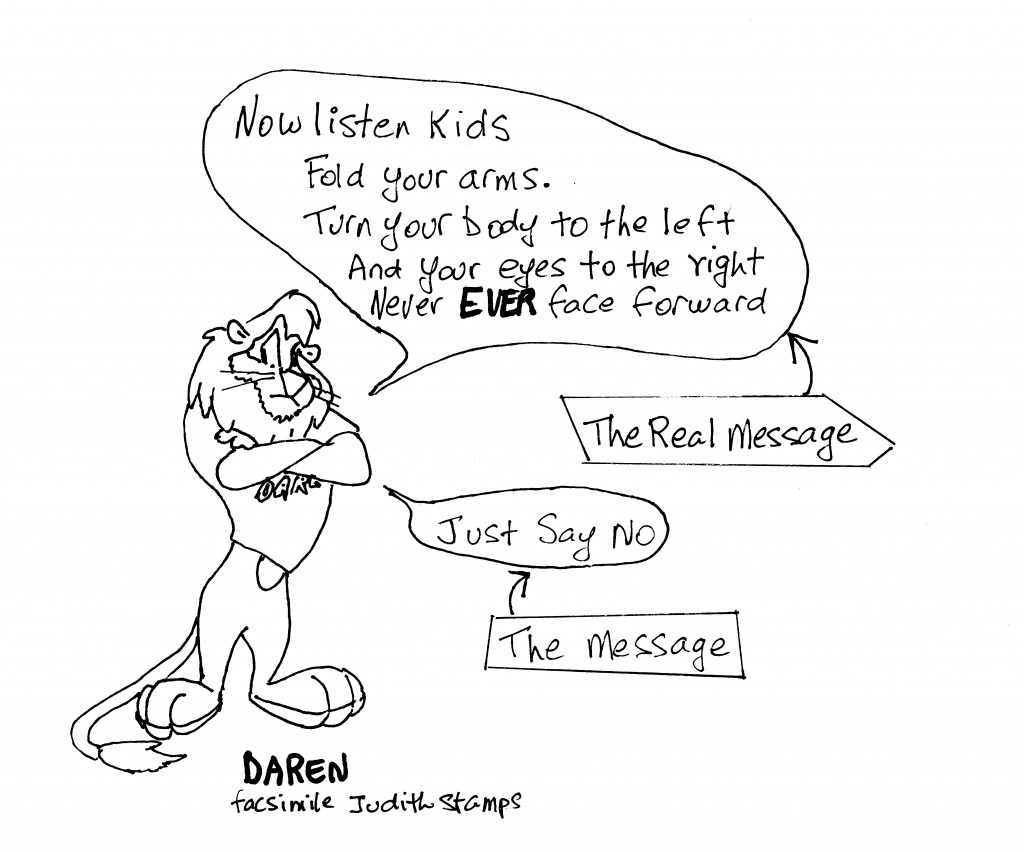

The organization has a good handle on buzz phrases. It claims to be ‘evidence-based’ and to teach ‘critical thinking skills.’ Its authors are masters of rhetorical framing. DARE workbooks for children offer instructive tales delivered by Yogi’s successor, Daren the Lion, a cartoon character drawn in the style of a super-hero. One such tale is My Trip With Daren. The story begins when Daren, a rank stranger, taps on a kid’s bedroom window. For reasons not provided, the stranger is invited in. The kid is nameless, so we’ll call him Kid. Once inside, the stranger announces that they will be going on a trip. Kid hops along. Daren’s trip, it turns out, is a series of conversations. The first one is about bullying. Daren tells Kid that bullies are everywhere, and that one must always report them. They wend their way next through a tricky conversation on theft. What do you do, Daren asks, if you see your friend steal money from the teacher’s desk? The answer is: you must inform the teacher without your friend knowing anything about it. You must do this even if the friend has asked you not to. They trod off finally to a conversation with Officer McCarty. McCarty caps the trip by reciting the eight ways to say ‘no’ to drugs. These include saying ‘no’ repeatedly, changing the subject, and walking away.

Thus framed, the drugs in this story are about bullying, and being bullied. They are first cousins of dishonesty and theft, and second or third cousins of covert reporting. Daren, though a stranger, is embraced as a brother. Kid will follow him anywhere. Officer McCarty’s ‘eight ways to avoid drugs’ mirror the anti-bullying techniques described earlier in the story. They are also remarkably like the standard techniques for avoiding spinach and brussel sprouts, so it is a mystery to me why kids needs to be taught them at all. In any case, this is what passes for critical thinking and evidence-based programming. It might be funny were it not so insidious. Children are encouraged, as Renaud has said, to turn in their parents.

For Herb Couch, DARE creates two additional difficulties. It is dishonest, and young people soon figure this out. They then lose respect for their schools, and for any authority on drugs. Second, it creates a loss of autonomy for teachers. They cede control of a key topic to the police, and tolerate a program in which many do not believe. Besides this, conservative groups claim to protect children. It is essential to Couch that EFSDP not relinquish this agenda to them. One way to maintain it has been to attend conferences of the BC Teacher’s Federation. This road has proven to be tough. Renaud spoke at the 2004 conference; there were 800 participants. The talk was well received. Thus encouraged, she returned home, and sent letters to 35 BC school superintendents, proposing alternative programs. All 35 said ‘no thanks.’ They had already adopted Daren. Couch attended the 2008 conference. There he was able to provide copies of a drug education booklet commissioned and provided by the Drug Policy Alliance. Authored by activist Marsha Rosenbaum, the booklet is called Safety First: A Reality-Based Approach to Teens and Drugs. Thus far, battling Daren has been slow work, and the results are unclear.

Teachers, says Couch, have learned to be passive resisters. Many reject prohibition, but rightly fear negative parent response. To date, EFSDP’s active membership remains small, and school response not as one would wish. For Herb, its future lies in communicating with Parent Advisory Councils. If parents and teachers form a single force against DARE, they might create the authority necessary to move beyond the War On Drugs. The program, I should add, is conspicuously absent from Vancouver, Victoria and Saanich. Elsewhere, for the moment, Daren rules.