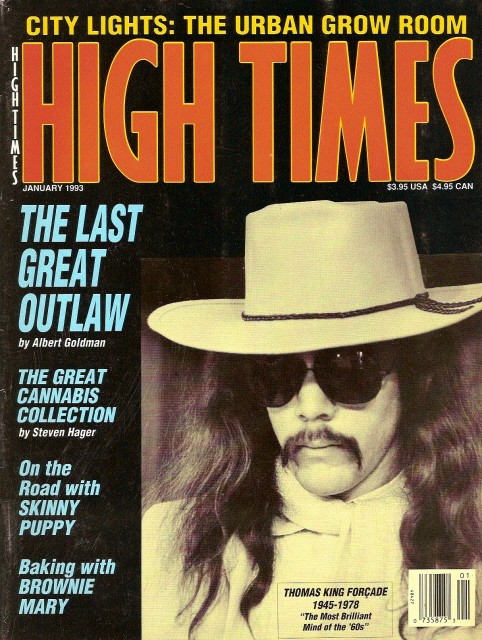

(High Times: Jan 1993)

By Judith Stamps

We remember Thomas King Forcade, if we remember him at all, as the creator of High Times, the Cannabis magazine that turned forty in 2014. We are unlikely to recall much more, however, as Forcade kept an aggressively low profile. His name never appeared on the masthead. He penned articles under fictitious names, Leslie Morrison, for example. When in 1978 at age 33 he committed suicide with a gunshot to the head, the mainstream media did not report it. Yet for the sixteen years between1962 to 1978, Forcade played a vital role in the new social and political movements of the era. Ambitious in spirit, he carried out key projects, skillfully engineered and long lasting in their effects.

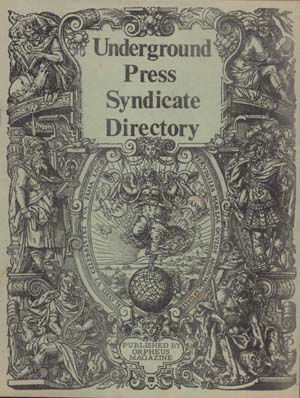

The earliest of these was Forcade’s self-published magazine, Orpheus, circa 1966.[1] Orpheus was a literary magazine, a broad compendium, with commentary, of articles Forcade had collected from the underground press. The publication proved to be an important training ground: when in 1968, the newly formed Underground Press Syndicate found itself rudderless, short-staffed and broke, Forcade stepped in as its national coordinator. Working initially out of a 1946 Chevrolet school bus, he established the UPS as a legal corporation, designed and printed an underground press directory, hired an ad agency, gained admittance for UPS journalists to the US Senate and House press galleries, and promoted membership. For $25.00 annually members agreed to send copies of their publications to all other members on the list. From then on alternative info was anywhere and everywhere. In an age before the Internet the UPS provided a lifeline. It kept activists’ organizations in touch with one another, fostering their sense of collective identity. Forcade funded this project in part by selling microfilm rights for all UPS publications to Bell and Howell, who then sold them to libraries. Thus by the same cosmic swoop he provided an archive for the future.[2]

The earliest of these was Forcade’s self-published magazine, Orpheus, circa 1966.[1] Orpheus was a literary magazine, a broad compendium, with commentary, of articles Forcade had collected from the underground press. The publication proved to be an important training ground: when in 1968, the newly formed Underground Press Syndicate found itself rudderless, short-staffed and broke, Forcade stepped in as its national coordinator. Working initially out of a 1946 Chevrolet school bus, he established the UPS as a legal corporation, designed and printed an underground press directory, hired an ad agency, gained admittance for UPS journalists to the US Senate and House press galleries, and promoted membership. For $25.00 annually members agreed to send copies of their publications to all other members on the list. From then on alternative info was anywhere and everywhere. In an age before the Internet the UPS provided a lifeline. It kept activists’ organizations in touch with one another, fostering their sense of collective identity. Forcade funded this project in part by selling microfilm rights for all UPS publications to Bell and Howell, who then sold them to libraries. Thus by the same cosmic swoop he provided an archive for the future.[2]

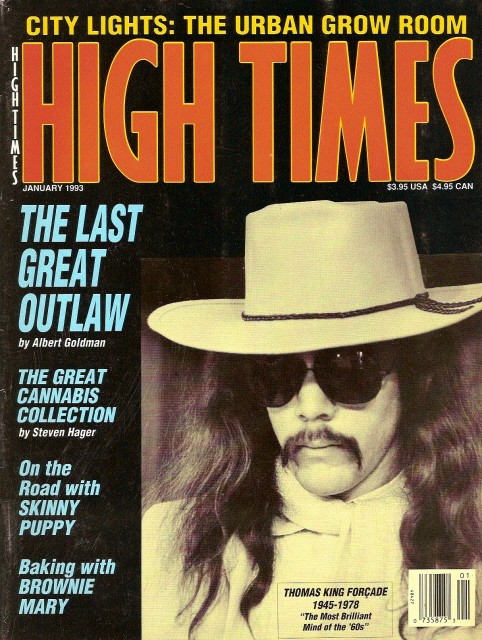

Localized, fractious and variable as they were, the activists of the 50s and 60s shared a consistent moral centre. They were anti-war and anti-racist; pro participatory democracy and pro freedom of expression. They were also pro cannabis. Attempts systematically to squelch their energy took two routes. One was to wage war against it; the other, to co-opt it. The first took the form of sapping publishers by dragging them into courtrooms on trumped up drug or obscenity charges, exhausting and expensive to fight. It cannot be overstated that from the 1950s onward, prominent writers of nonconforming material in North America were kept in a state of siege. Federal agents raided their offices and confiscated their material. Unknown persons firebombed their premises and smashed their windows. Hostile businesses intimidated their printers. Hostile governments intimidated their advertisers. When all the rest went well, local police harassed their street vendors.

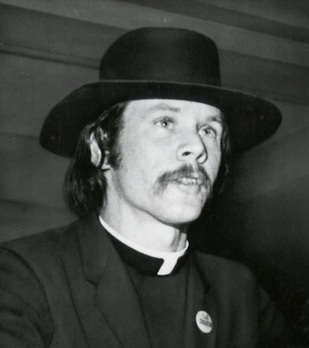

Forcade had the fortune, or misfortune, of working in the era during which President Nixon was preparing America’s forty-five year war on drugs, a plan that included an undeclared war on free speech. When in 1970 Forcade testified before Nixon’s Commission on Obscenity and Pornography he stunned the commissioners with a lengthy, prepared oration—a fusion of poetry, rant and High-Church liturgy, of which the following is a small excerpt. For several minutes commissioners were treated to this. “We are the revolution, these goddamned papers are our lives, and nobody shall take our lives away with your goddamned laws. We are tomorrow, not you. We are the working model of tomorrow’s paleocybernetic culture, soul, life, manifesting love, force, anarchy, euphoria, positive, sensual, communal, united, brotherhood, universal, organismic, organic, harmonious, flowing new consciousness media on paper, coming from our lives on the streets. So fuck off, and fuck censorship!”[3] This last phrase, repeated five times during the speech, served as universal chorus.

Speech completed, Forcade dumped a whipped cream pie onto the head of Commissioner Otto Larsen. Was this performance effective? It probably was as much as anything else in the 70s. And for a while afterward ‘pieing’ for political effect became a ‘thing.’

Then there were the attempts to co-opt. Later that year Forcade learned from Warner Brothers’ ‘hip’ recruit Michael Forman that WB was making a road movie modeled on Ken Kesey’s historic bus trip from California to New York, with staged concerts added. The corporation wanted to capitalize on its success in filming Woodstock.[4] The new film, Caravan of Love, was to be directed by Francois Reichenbach, a Frenchman for whom the 60s in North America was an alien planet. His finished picture was to be empty of political content. There were 150 participants, some genuine counter-culturists who dreamed of winning control of the film by counter-co-opting. Forcade elected to join the Caravan, intending to do something similar. He arrived on site in a 1965 black Cadillac limousine onto which he had bolted a stage and a sound system with enough wattage to shred the universe.[5] He deployed the speakers, rattling the cage. He staged alternative music, muddling the manufactured image. He tried his powers of persuasion on Warner Brothers staff. He told them that New Yorkers would dismiss an apolitical Caravan as an exercise in escapism. More importantly, he and the Cadillac embodied a liberated zone—a retreat for participants feeling more and more choked by an ignorant and hostile media environment. He recorded the event in a charming but searing paperback, worthy of republication.[6] Meanwhile the movie was released.[7] A heavily clichéd, fake documentary with no clearly imagined audience, it flopped.

Then there were the attempts to co-opt. Later that year Forcade learned from Warner Brothers’ ‘hip’ recruit Michael Forman that WB was making a road movie modeled on Ken Kesey’s historic bus trip from California to New York, with staged concerts added. The corporation wanted to capitalize on its success in filming Woodstock.[4] The new film, Caravan of Love, was to be directed by Francois Reichenbach, a Frenchman for whom the 60s in North America was an alien planet. His finished picture was to be empty of political content. There were 150 participants, some genuine counter-culturists who dreamed of winning control of the film by counter-co-opting. Forcade elected to join the Caravan, intending to do something similar. He arrived on site in a 1965 black Cadillac limousine onto which he had bolted a stage and a sound system with enough wattage to shred the universe.[5] He deployed the speakers, rattling the cage. He staged alternative music, muddling the manufactured image. He tried his powers of persuasion on Warner Brothers staff. He told them that New Yorkers would dismiss an apolitical Caravan as an exercise in escapism. More importantly, he and the Cadillac embodied a liberated zone—a retreat for participants feeling more and more choked by an ignorant and hostile media environment. He recorded the event in a charming but searing paperback, worthy of republication.[6] Meanwhile the movie was released.[7] A heavily clichéd, fake documentary with no clearly imagined audience, it flopped.

Forcade was also a major plant smuggler, hence, probably, his low profile. He was known to import carloads, truckloads, and planeloads of Cannabis from Mexico to the US. He had a reputation for Robin Hood-like generosity.[8] He was a strong supporter of NORML. But as his biographers have noted, smuggling consumed him and made it difficult for him to sustain the political communication in which he so deeply believed. He was known to disappear for weeks, and suffered from fits of depression and mania. Biographers Steven Hager and John McMillian have wished aloud that Tom Forcade had saved his energy for his writing and oratory. Uniquely perceptive, he could have been a voice for his generation.

But Thomas Forcade was cursed with the gift of spectral vision, a state sufficient, in my view, to prevent him from being such a voice. In 1970, prior to joining The Caravan, he had attended an underground media conference with 3,000 participants. On afterthought he had this—admittedly substance-enhanced—three-dimensional analysis to offer. 1. This conference has been called “little Woodstock.” It was, but mainly in the sense that the media about the event was the event. 2. The underground press is now run by a series of mafia don equivalents, and this conference determined who controlled whom, and through which alliances. 3. The sub-groups of the movement—the Yippies, the spiritualists, the communes, etc.—are now a series of franchise operations. This conference was a trade show.[9] Later, a historian documenting Forcade’s response to government harassment noted this range of attitudes. 1. These guys are trying to kill us. 2. Actually that‘s good. They’re taking us seriously. 3. Besides, we’re amazingly resilient. 4. On the other hand, their distribution monopolies are going to choke us to death. 5. Still, I wouldn’t be surprised to see us blossom into dailies.[10]

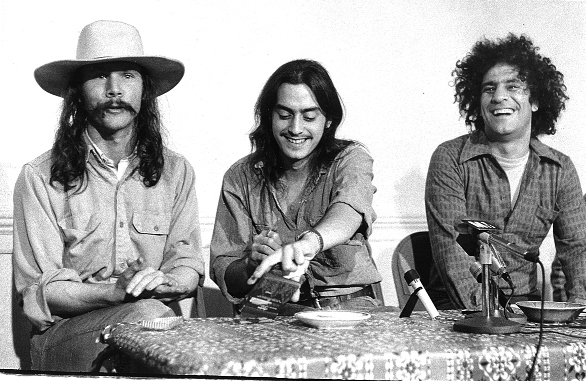

(Tom Forçade, on left, in 1971, with Mayer Vishner and Abbie Hoffman.)

As an activist he supported optimism. But tucked behind Forcade’s thick layer of bravado was a hardheaded curmudgeon. He was sympathetic to magical self-liberation but also to the certainty of doom. He was sensitive to bullshit. He supported ‘the revolution’ but saw living institutions as bundles of attitudes ranging from benign to pernicious. There was no compelling reason, thus, for him to choose writing as a central activity. Importing marijuana would have seemed just as essential. At least it was something material. In any case had his writings been more visible, they may have found a less than enthusiastic response: he could paint very unflattering portraits.

But he loved journalism, and in the last four years of his life, he created and published High Times. Wikipedia has suggested that the magazine survived in part by feigning the look of an entertainment rag.[11] The writer has a point. High Times featured ads for music and pot paraphernalia. It had photos of expensively dolled up but ill clad women that looked like strippers. It paired reefer with lipstick, and bongs with high heels. In touch and feel it echoed the crassness of much commercial publishing. When placed on a newsstand, it blended. So when it offered serious accounts of the best growing techniques—Ed Rosenthal was an early, regular contributor—this feature seemed somehow less than obvious. Of course the magazine was still hassled. But it prevailed, and at least until the early 2000s, offered serious alternative journalism. If it has since become blander it’s at least still here, and now in the company of many such publications, both in pulp and online.

Today, High Times is equally in the company of epic changes in cannabis law reform. If Forcade were here he would surely say: We’ve done it. We’ve freed the plant. Oh, and let the seduction begin. Here comes Cannabis, the Movie.

[1] http://www.afka.net/mags/Orpheus.htm

[2] https://www.smashwords.com/extreader/read/282264/1/the-last-great-outlaw

John McMillian, Smoking Typewriters: The Sixties Underground Press and the Rise of Alternative Media in America, Oxford University Press, 2011, pp. 123-125.

[3] McMillian, 137-139.

[4] Thomas King Forcade, Caravan of Love and Money: Being a Highly Unauthorized Chronicle of the Filming of the Medicine Ball Caravan, New American Library, 1972.

[5] Forcade in Ibid, p. 47.

[6] Caravan of Love and Money is out of print, but findable through Abe Books.

[7] The released film was called The Medicine Ball Caravan. http://www.thevideobeat.com/music-documentaries/medicine-ball-caravan-1971.html

[8] Albert Goldman in “the last great outlaw.” See endnote 2.

[9] Forcade, Caravan of Love and Money, pp. 26-29.

[10] McMillian, Smoking Typewriters, p. 136.