The recently held First Annual Conference of Sensible BC featured a great menu of panel discussions and small study sessions. One of the truly enjoyable subjects on the menu was how best to imagine life in post prohibition Canada. In this context, Marc Emery reiterated his view that we should legalize the plant and impose no regulations. Kirk Tousaw, our lawyer in residence, reminded us that we should expect regulations along the lines of those in place for tobacco and alcohol. Dana Larsen expressed the hope that cannabis growing and processing would come to resemble wine production, with its tradition of sommeliers, well-toured wineries and home brewing. A more unusual set of ideas came from Mark Haden, long time anti-prohibitionist and Adjunct Professor of the UBC School of Population and Public Health. I should say that I had already encountered Haden’s view in a recent publication in which he argued that future marijuana stores should be intentionally boring places, located above street level. I was startled by these words, and at the conference I attended his lecture in order better to understand what he had in mind. In today’s blog I would like to summarize his message, and then consider its suitability to the issue of marijuana today.

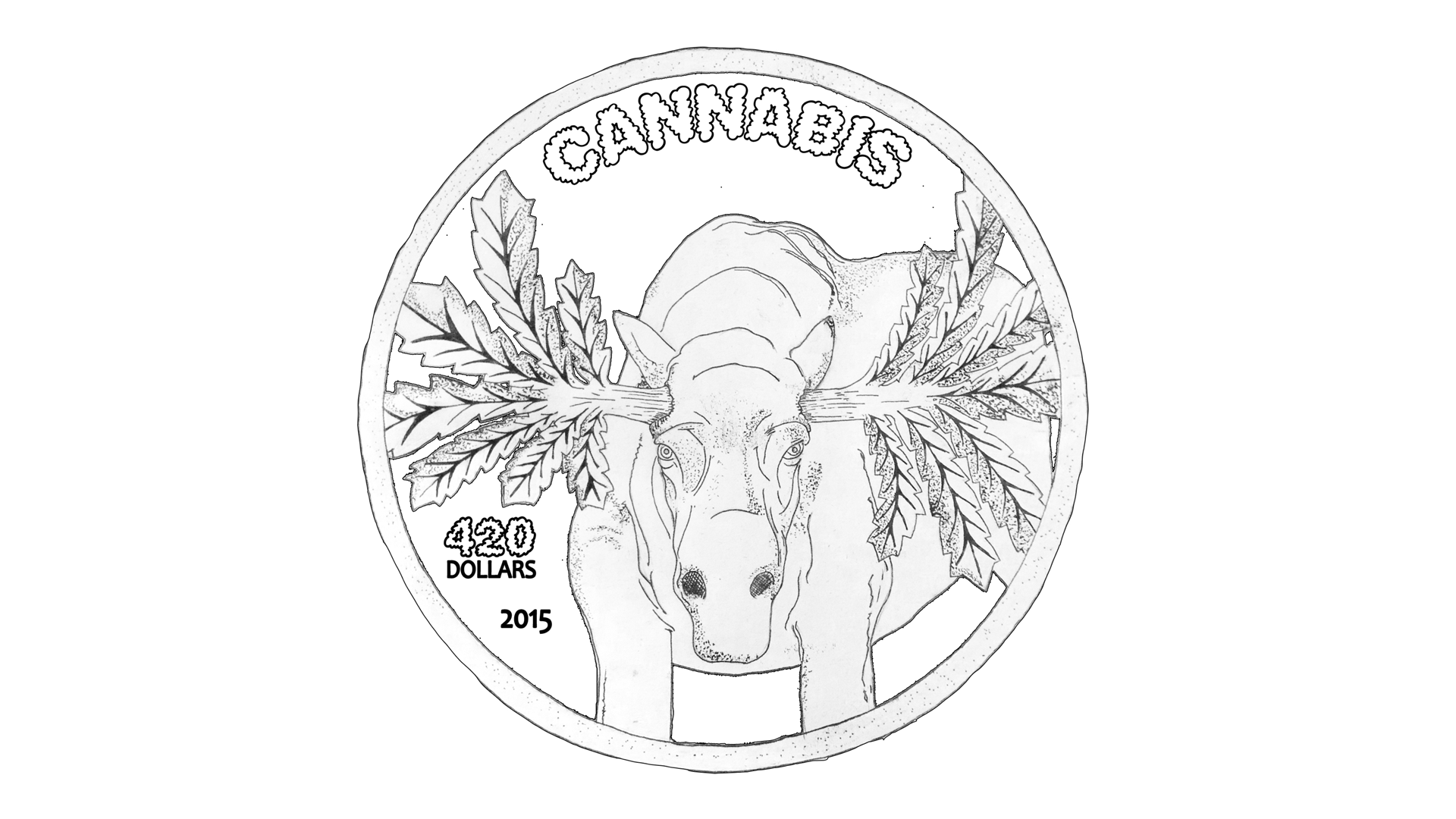

According to Haden, it is essential that marijuana activists and policy reformers learn lessons from the history of alcohol and tobacco. If we don’t we will simply be reproducing a system that damages personal and public health. Those lessons, in Haden’s view, centre on product advertising and in particular, branding. In a corporate society companies brand products the better to advertise them, and then work the ads to drive up consumption, the better, in turn, to drive up profits. In the tobacco and alcohol industries, this process is already in full force. With marijuana we have a chance at prevention.

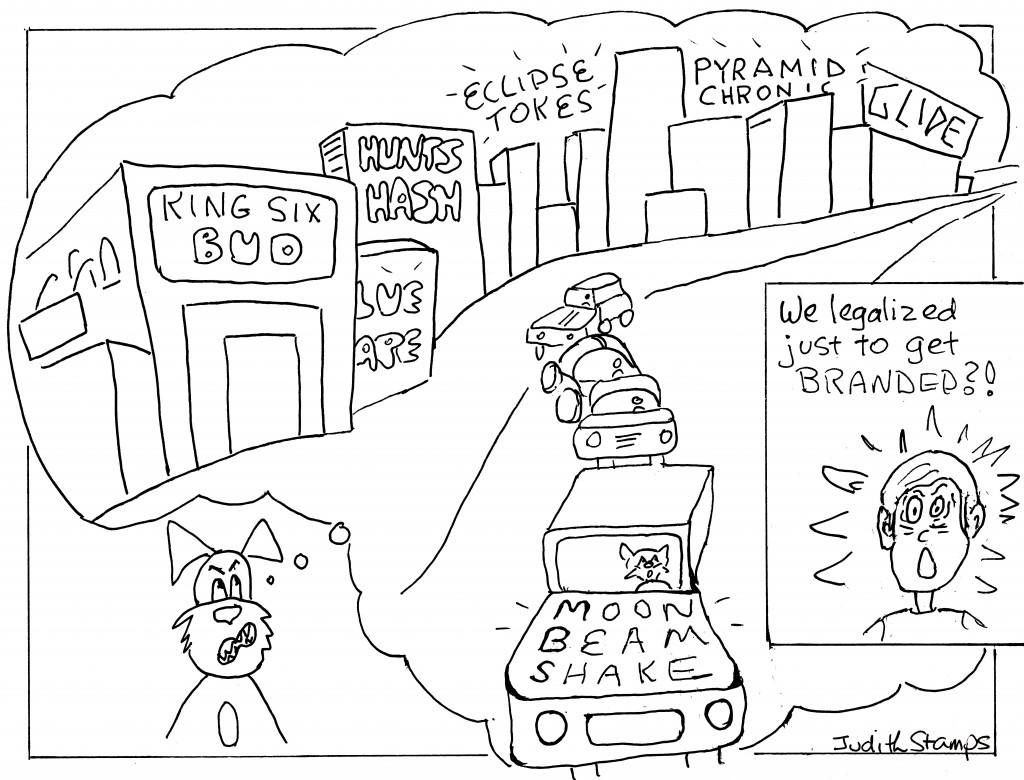

To this end, Haden suggests that future marijuana shops be designed as ‘neo-apothecaries.’ He didn’t elaborate—I suspect we kept him too busy with our questions. So let me suggest what he might have had in mind. Haden’s apothecary would be out of the way, maybe even above ground level on an upper floor of a building. The shop would have bins of bud and other assorted goodies with no brand names, and no fancy packaging. There would be little signage other than the minimum required to indicate cannabis strains, edibles and other things on offer. Vapourizers, hash makers and suchlike are already branded, but he’d probably let that pass. General laws would prohibit branding cannabis or its derivatives. The resulting shop would look like a pleasant cross between the Victoria Cannabis Buyer’s Club medical marijuana dispensary and my favourite coffee bean store. The VCBC’s sign reads: Under Renovations (sic); and the coffee store’s, Yoka’s Coffee.

How should we view this model? Some of its elements are trendy: think tea stores or an altered Bulk Barn. Some shopkeepers might like it. But it is problematic, in my view, to require or even urge all shops to resemble this one. The mandatory apothecary model grows out of Haden’s comparison of marijuana to tobacco and alcohol. I do not agree that this comparison illuminates a great deal about marijuana and its future. Here is how I see it. Alcohol was prohibited for less than a generation; tobacco not at all. Its image never got ugly. Marijuana bears a stigma that goes back at least a couple of hundred years. In Mexico, the Middle East, in India and elsewhere, not to speak of North America, the plant has been associated with members of ‘degenerate’ races or classes, and later, with groups looked upon as wrong–headed and unpatriotic. We have no living memory of marijuana in a free setting, and no historical examples, so the stigma is deeply, culturally embedded. That this is so can be seen from the examples of Colorado and Washington State where, after legalization, over half the local jurisdictions banned shops. Sizeable chunks of their respective populations have a visceral hatred for marijuana. As many of us learned through the Sensible BC campaign, large swaths of BC residents feel much the same. So do portions of other provinces. For pot fans, it’s a struggle just to feel normal.

So suppose we try to mandate the apothecary model described earlier. Marijuana vendors alone will be relegated to marginal, nearly unmarked locations. They won’t be making a choice. Moreover, while they and their stores will be rendered invisible, the restrictions placed on them will be widely publicized. They will look collectively guilty, as they always have. They’ll remain stigmatized. They’ll have a harder time than ever finding friendly landlords and businesses willing to have them as neighbours. They may be forever unwelcome in downtown business associations. We can’t have that.

Then there is fact that marijuana fans are a zany and irrepressible lot with a scary and painful past. If post prohibition we set out to suppress their energy, we’ll only be poking them with a sharp stick. If we do that we’ll have them screaming, and do little good otherwise. It will be hard enough for them accept incremental change. It will be way too much to accept being beige

In designing something for the future, it is important to begin by seeing that over the past eighty plus years, marijuana prohibition has engendered a large community, something that never occurred around alcohol. There are recreational growers, hemp growers, medicinal growers, processors, vendors, musicians, artists, amateur chemists and medicine makers, publishers and writers of blogs, maintainers of dedicated websites, online archives and libraries, adjunct lawyers, front line warriors, and producers of street theatre. Together they have created an impressive string of court cases and legal decisions. The literature by and about them would fill a small bookshop. Although this world is not homogenous, there is a shared sense of identity. But this identity has never been integrated in a constructive manner with its wider social surroundings. Recent history has shown us that legalization stops the arrests, and establishes the beginnings of a framework. But that’s all it does. It’s only after legalization that the real work—forging a new relationship with society—begins. In this process there will be a place for well-designed ads.

Let’s look more closely now at advertising and its evil twin, branding. Advertising emerged historically when comestibles and other products left the home and home workshop, and entered general stores. At that point the stores required signage and, as they grew larger, catalogues. Those are forms of advertising, although fairly benign ones. But when flourmills emerged to compete with one another, they touted their own brands, leading us down a path that has been less than healthful. Where products are alike, as they often are, buying brands amounts to buying words and images. Words and images can be designed to prey on our insecurities, and insecurities can lead us to buy what we don’t need and can ill afford. Haden notes that prohibition wrecks the natural controls that keep consumption in check. I think he would agree that branding does something similar for the individual. The louder the words and images, the dimmer the inner voice that tells us when we’ve bought or consumed enough.

But let’s look now at the real situation facing us. Wherever marijuana is presently legal, almost all advertising of any kind is forbidden anyway. Colorado’s marijuana businesses are fighting the ad restrictions. Others will follow. They need acceptance, and they won’t get it skulking off to remote corners. Alcohol consumers could use less aggressive glitter. Right now, pot fans could use more. Further, it took two post prohibition generations for alcohol ads to become obnoxious. Given the opposition to marijuana, it may take many generations before we’ll see many ads or the problems that attend them. Still, as there is merit in the view that branding is bad, we should consider how much to worry about fending it off.

Because it is widely recognized as a medicine, marijuana is unlike alcohol or tobacco. For medicinal users, branding is currently irrelevant. Their overwhelming need is for particular strains bearing natural names, and for repeatability. For this reason, Canada’s licensed producers have chosen to stick with the familiar. So have the unlicensed ones. No one is making proprietary blends and, aside from the odd bit of Facebook hysteria, there has been no talk of creating new, patentable strains. In any case, at this stage repeatability is very limited. It’s nearly impossible to produce any two Purple Kush plants with identical cannabinoid profiles, even when they are grown under similar conditions. It’s not clear to me that these plants will be candidates for branding any time soon.

One of marijuana’s special features is its ability to induce mind states that range from sleepiness to wide-eyed wonder. It can also reduce pain and inflammation. Since many recreational users will know patients, and most will at least know of the plant’s medicinal values, they too will be interested in specific and recognizable strains. Who doesn’t need a sleeping potion from time to time, or a chance for a fresh perspective? For these reasons marijuana will resist branding in a way that alcohol never could. What’s odd about branded goods is their similarity. Vodka is mostly just vodka. Marijuana varies.

Still, we will eventually be facing danger from investors. They’ll know nothing about Purple Kush, and they’ll want to brand. So what can we do? We cannot prohibit branding. That’ll work as well as every other kind of prohibition. But we can take a different lesson from history. Ads emerged historically when products for personal use became products made to sell in stores. One thing we can do, for which there is already precedent, is to encourage home growing. We can foster a culture of home gardens much as we do today with fruit and vegetable gardening. We can encourage magazines, garden shops and educational seminars. We can encourage small growers and farmers’ markets. We already do that for other crops. This practice may not supply all or even most of our food, but it does alter people’s notions of what is desirable, and what is ‘cool.’ It even alters what we find in the large markets. To the sizeable anti-pot brigade this idea will be a hard sell. In Canada, the RCMP has worked hard to convince whole neighbourhoods that pot plants cause house fires, and canna-butter, meth lab style explosions. For governments keen on their tax money, encouraging gardens will require a compromise. But it’s probably doable, it will make the plants universally affordable, and we’ll have the pot fans and their friends on side.

Another important strategy will be to make sure that current, talented but illegal growers have a way to buy into any future legal system. Rules that eliminate good growers because they have criminal growing records are not sane. Health Canada’s rules that require a ten million dollar business plan in order to meet government standards are not sane either. For four generations, the best growers have done what they do for normative reasons. No one in the current movement is keen on branding if only because it drives amalgamation. Besides that, it’s crass. If as a public health expert Mark Haden has a chance to bend the ear of a new legalizing government, he might encourage them to let this generation of growers and processors lead the way. They’ll resist branding, and they may even influence future generations to do the same.