Many readers will be familiar with the story of America’s War on Drugs. As most of us know it, the story goes something like this. Following political upheavals in Mexico in 1910, large numbers of Mexicans immigrated to the US, especially to the Southwest. For predictable reasons, the immigrants became objects of contempt. They spoke a foreign language; they were dark skinned; they took low paying jobs. Moreover, they brought with them the practice of smoking weed. No one wanted them around, so both they and their practice were condemned as alien and harmful. The ‘alien’ notion was then boosted by the birth of Jazz in the 1920s, particularly by the emerging news that Black musicians and their admirers were fans of reefer. Then in 1930, American prohibitionist Harry Anslinger was appointed chief commissioner of the newly formed Federal Bureau of Narcotics (FBN). Within a couple of decades Anslinger and his crew had dreamed up Reefer Madness: the familiar stream of lurid tales that peppered the Hearst press throughout the 1940s and early 50s. As we currently understand them, these tales were invented by the FBN.

But it turns out that they were not invented by the FBN. They were not invented in America at all. The lurid tales were created in Mexico by Spanish-Mexican prohibitionists in the late 19th century, and only later copied by American journalists. This new fact is the subject of Mexican scholar, Isaac Campos’ recent (2012) work, Home Grown: Marijuana and the Origins of Mexico’s War on Drugs. Based on analyses of Mexican newspapers in the 19th and early 20th centuries, Campos’ study tracks the development of the original reefer madness in Mexico. Rooted in Mexico’s medical history, this reefer madness succeeded, by 1895, in convincing Mexicans that marijuana was the province of the violent and the insane; and by 1920, in bringing about marijuana prohibition in that country. In what follows, I offer a summary of Campos’ account.

One must begin, in Campos’ view, by discarding the idea that recreational marijuana is a casual, traditional part of Mexican life, something like coca leaf chewing in Peru or khat chewing in Djibouti. It has never been that. Recreational marijuana in Mexico has been traditional to two groups only: the inmates of Mexico’s prisons and the soldiers living in its barracks. Neither group was well thought of; both were known for senseless violence. There were, in addition, native peoples that used marijuana for medical and religious purposes. They were not violent, but the Spanish-speaking Catholics rejected their religious ideas, and the dominant Spanish medical practitioners rejected their healers. One way or another, ‘proper Mexicans’ did not embrace marijuana as something good for recreation. Rather, they associated it with bad living.

Mexico did, however, have a medical marijuana tradition, much like that in other countries in North and South America, Europe and Asia. In 1842, marijuana was listed as a narcotic in the new Farmacopoeia Mexicana, where it was itemized both as Cannabis Sativa: cañamo, and Cannabis Indica: mariguana. But its distribution was highly restricted. Medical practice in Mexico followed the traditions of Spain, and Spain had a longstanding love of strict regulation, rooted in its mediaeval past. In mediaeval times, Spain had served as the world’s harbor for Arabic scholars. From the fall of the Roman Empire to the expulsion of all non-Catholics from Spain in 1492, those scholars were the keepers of Western knowledge. They studied the Greek and Roman medical texts, and translated them. They shared their studies with the Christian and Jewish scholars that lived among them. As a result, Mediaeval Spain had a set of medical practices far in advance of anything available in the rest of Europe.

It also had a highly advanced system of regulation. By the early 1500s, for example, Spanish laws were in place to oversee and regulate all medicine and pharmacology in that country. There were national inspectors who paid regular visits to Spain’s physicians and apothecaries. There were laws for controlling access to medicines. In this world, physicians ruled. They wrote the prescriptions; Apothecaries dispensed only what had been prescribed. After its independence in1810, it was this system, deeply rooted in Spanish-Arabic history that Mexico chose to adopt. The system provided Mexican patients with medical marijuana, but only via prescription. It allowed prescriptions, but only from western style physicians.

Mexico had not adopted these rules with recreational users in mind. The rules were there simply to protect the authority of western medicine, and western medical men. But in practice, they served a dual purpose. Once in place, they allowed for easy prosecution of locals who liked to smoke. So by the time of the widely attended Hague Opium Convention of 1912, which recommended regulation, Mexico, with its Spanish background, was well ahead of the game.

Regulating marijuana was spurred as well by Mexico’s adoption of The Social Hygiene Movement, a set of ideas popular among emerging nations. Social Hygiene was based on the view that ‘modern’ science should be used to cleanse and perfect society; its methods should be used to select the ‘better’ social classes and reject the ‘degenerates.’ Followers of the Movement believed, in addition, that degenerate behavior in parents was physically passed on to their children. This notion stemmed from the work of Lamarck, a popular evolutionary theorist. According to Lamarck, actions in life alter genes. Mexican elites embraced this idea. They argued that pot smoking among Mexico’s prisoners and soldiers was making them worse. It was unraveling their genetic material, causing them to father crazy kids. In this way, it would soon corrupt the country, leaving Mexico a nation of despicable wretches.

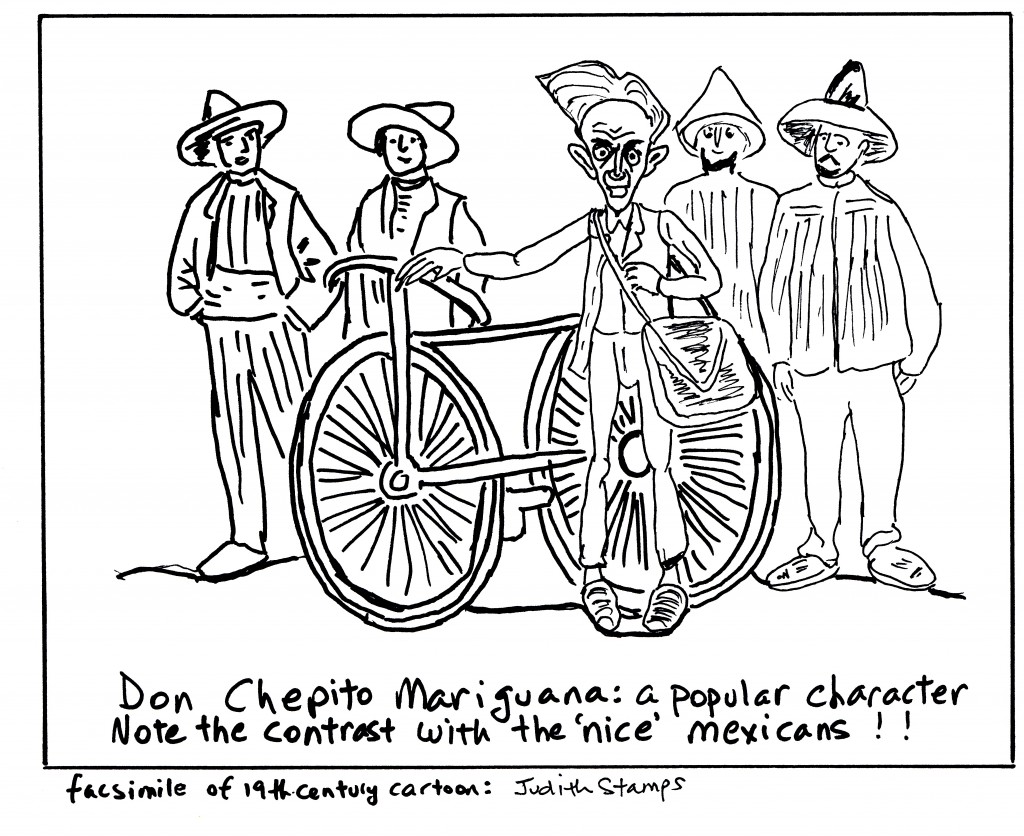

Similar ideas were repeated and popularized in Mexican newspapers of 19th, and early 20th centuries. They developed a special fondness for stories about violence among Mexico’s pot-smoking prisoners and soldiers. They fostered the belief that marijuana and bloody knife fights went hand in hand. They popularized dope fiend cartoon characters, drawn to look bug eyed and bizarre. My accompanying cartoon, copied from an original featured in Campos’ book, shows the popular figure of Don Chepito Mariguana, a genetic misfit if ever there was one. Near the turn of the century, these messages went international. In 1895, The Mexican Herald began to publish an English language newspaper. As the Herald also held the Associated Press franchise for the Mexican capital, its stories were easily reprinted or reworked by American journalists. A Story retold in a Salt Lake City newspaper in 1898, for example, described a marijuana crazed boy who ran amok, tearing off his clothes and attacking passersby in the main street of his town. Other, similar stories made their way into American culture. In Campos’ words, “It was from this atmosphere that the US media began to pluck exotic, sensational stories of the new drug menace south of the border.”

To make matters worse, turn of the century America was much concerned with a problem plant called ‘locoweed.’ Locoweed is Jimson Weed, Datura Stramonium. When horses and cows graze on it, they go crazy. Press stories of the day confused marijuana intoxication with the effects of locoweed. Some readers thought that locoweed was marijuana. The term locoweed contains the Mexican word for ‘crazy.’ One can well imagine the effects caused by this kind of confusion. It is no wonder that Mexican immigrants were unwelcome in the US post 1910. Nor it is surprising that, from 1915 onward, individual states began to pass anti-marijuana laws. With the locoweed notion flying around, and all the preceding, neither the immigrants nor the plant would have stood a chance.

Put these elements together—restrictive medical practices, the use of marijuana by ‘social misfits,’ Social Hygiene ideas, locoweed, and the press—and you have Mexico’s original Reefer Madness. It was from these elements, and from Mexican sources, in Campos’ words, “that the US government and the press first heard that marijuana turned ordinary people into ferocious maniacs.” With these facts in mind, we fans of Cannabis must now review and reject the standard, well-boiled Reefer Madness stories on which we have been fed. Whether we are Cannabis historians, prohibition history freaks, or simply people who like to remember the old Reefer Madness story, we might also like to ask this question: where does all this leave old Harry Anslinger? Readers will choose their own answers; I say it leaves him every bit as mean, and a lot less inventive. It turns out that he didn’t need imagination; he just had to read the old papers. As to the immigrants, some of them obviously did use pot. And after American prohibition in 1937, their home country did become a key source of the plant. Regardless, it is now our turn. Those of us with a passion for understanding the past must work to make the necessary mental adjustments.